Civilisational Success, and its Dangers

by The Editor

Guest contributor Rupert August discusses the nature of civilisational decline and its lessons for contemporary Great Britain.

Innovation, broadly defined in economic terms as: improved efficiency through greater output attained with the same amount of resources - is conventionally seen as a unqualified ‘good’. This is an incomplete definition, but this, rather than the inventive method which creates entirely new entities, is the prescient part of this article. Indeed, it is often touted as the primary benefit of the free market to promote such innovation. Less commonly discussed are the parallels of this idea in the cultural sphere. This interaction will take a similar form, but let us distinguish it like this: a cultural innovation is one which allows for the same level of utility or satisfaction to be obtained from a smaller input. This may appear to be true also in the case of economic innovation, but this distinction is made in the case of cultural innovation because of the seemingly universal (at a population level at least) desire for comfort, and effort minimisation. A frequent example of this may be the delegation of policing or defence duties to a dedicated body, rather than handling the matter locally, thus generating the typical economic benefits of specialisation and division of labour. Simply by using this example, some of the issues to be discussed may become clear, but considering the delegation of such matters are not usually conducted in quite that fashion, another may be useful. Over time we have become accustomed to a certain level, and a certain kind of nutrition. The benefits of this have been a general increase of welfare, as well as physical and mental improvements which have improved our lifespans, intelligence, vitality and health. When we are put into situations where these expectations cannot be met, therefore, we have more difficulty in operating. Larger bodies require more sustenance, and accustomed minds will resent the lack, such that men thrust into either the jungle, or desert in wartime will require more logistical support to achieve the same level of effectiveness. Not only this, but there is a perfectly logical tendency to tame the inhabited landscape over time, either through urbanisation, or domestication of the countryside into an easily workable form such as the English countryside. Both of these measures are perfectly reasonable developments, particularly because stable peacetime - where most of the benefits, and the fewest number of drawbacks to these innovations are felt - is most of time for most people. Yet, when war comes, and these propensities are challenged by circumstance, the hardier people will gain a great advantage.

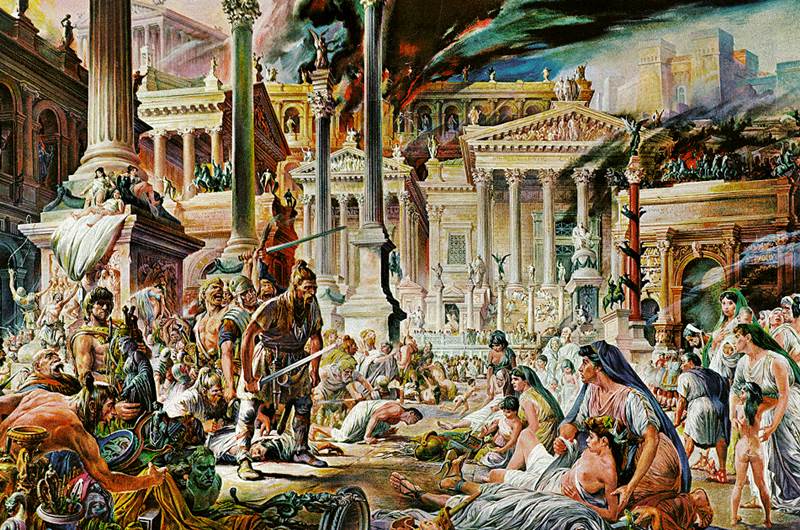

So even if we were to accept this as true, what would be the consequence? Well it might go someway to explaining why civilisations can appear to collapse so quickly, particularly in relation to their slow growth. Likewise why there is a persistent concept of moral degeneration preceding a collapse. Hard work and little leisure time are necessary for a poverty stricken people, but as society develops the possibility of allowing a greater number of people to enjoy more leisure, and less work, then resisting this development will prove incredibly difficult. But in the wake of this first case, a precedent will be set, that will strengthen the argument of any who would champion yet further leisure. As this continues, however, the expectations raise with it, such that any suggested reductions, even to the same previously enjoyed level, will be considered disastrous, and avoided at all costs. When this tendency is set in stone, literally in many cases by the movement of peoples both geographically and between trades, the consequences are even more keenly felt if the supply is disrupted. During the earlier years of Rome, the city’s grain supply was amply managed by the countryside in its own proximity. But as the city grew, and new territories were added, areas more and more further afield were enlisted to fulfil the task. And why should they not? Rome was less fertile than Sicily, and the North African coast around Carthage more fertile still. It is perfectly logical, then, to supply Rome’s capital, notably the grain dole, using North African yields. The price will be low, because the yields are high, and stability will be maintained among a potentially rowdy and growing population. Yet doing so opens up the method by which Rome might be brought to its knees, as the loss of North Africa, and its reconquest marked one of the defining objectives of a Western Roman empire on its last legs. For letting it remain outside of Rome’s control would be a consignment to the whims of the new occupier as a result of being so reliant on their trade, or a major economic and lifestyle shift from a nearly 600 year status quo. Though it must be noted that this was not the inciting incident of Western Rome’s final dissolution. That beginning can be more conceivably ascribed to when Alaric’s visigothic army numbering fewer than Hannibal’s after Cannae, faced a city which was much larger, and had not suffered an immediate prior catastrophe such as that of Cannae, yet Alaric sacked Rome, where Hannibal had not dared to begin a siege. A consequence of Roman outsourcing of the military for centuries, perhaps?

All of this is to suggest that these advancements may not be entirely without cost. And although it would be a difficult argument to make; that one should deliberately turned away from such things, there may be an argument to make there. At the very least, perhaps, maintain contingents that may keep older ways alive, so that they may be revisited in the event of some catastrophe which reveals their utility. And that this be maintained regardless of the situation elsewhere. The rational thing to do, economically, would be to tarmac over near enough all of England, and have it all be housing, industrial, and commercial properties. The infrastructure would be much improved, housing would no longer be an issue for generations to come, and foreign capital would be plentiful, all other things being equal, in the face of drastically reduced land and transportation costs. Furthermore, all of the labour otherwise wasted in a comparably inefficient sector - agriculture, will be saved, and repurposed towards more efficient uses. If this is not immediately repulsive, then perhaps consider: should we, in the British Isles, face an international food trade disruption, caused by any number of factors, we would already be in crisis trying to feed the current population. This can only be worsened (all other things being equal,) with any further movements towards the extreme mentioned earlier.

With all this said; that rational decisions made in accordance with sound principles for the majority of cases yield situations in which a crisis is either created or drastically worsened upon its appearance, it is yet possible to go further. If a people who are more poor, less numerous, and even less fearsome than their neighbours were to make any wrong move with regards to their collective conduct, and belief system, they would be weakened much more obviously by it. A people so close to extinction could not make such a mistake if it is to continue existing. Even without neighbours to act as such a threat, the proximity to death created by an unforgiving environment is its own insurance that one must follow a true set of practices. Failing that, a selector for those ideas which convey strength, by forcibly removing those which grant only weakness. In doing so, those that pursue these strengthening ethics gain power and material advantage; land, wealth, manpower, technology, and more. But with these additions, the need to stay so closely aligned to those strengthening ethics is weakened, as straying will no longer be so obviously punished. A culture still in practice is a living culture, and thus one which may mutate over time. As such, ideas and ethics may become firmly nested in a culture and people, which, far from granting strength, detract from it. But often, so great is the magnitude of the people’s earlier achievements that many generations may pass before the culture steps out of their shadow. By that time, parasitising ideas may be so firmly rooted that they are considered almost foundational, or at least key to the civilisation itself. Certainly this seems to be a primary feature of the historic ebbing and flowing of Hellenic civilisation - ever jostling between fierce in-fighting, and unity. Though unity is by no means always advantageous, it was the difference between victory and defeat against the Persians, Macedonians, and Romans. Even later under the Byzantine Empire, the Hellenes faced this same conflict, and often with similar results. During the final Byzantine-Sasanian war in 602-628, unity snatched victory from an already cataclysmically lost war. Meanwhile in the aftermath of a defeat with relatively minor losses at Manzikert, the subsequent civil war afforded the Turks an opportunity to deal a blow from which the Byzantines would never fully recover. We can hazard a guess as to what the average citizen at the height of democratic Athens might think of tyrants and despots, even though their own Mycenaean descendants served their kings as, by the Athenians’ definition, little more than slaves. So likewise, was it the artistic ethic of the French that made them strong? Was it the Russians’ stoicism? What about the Swedes’ tolerance? These are somewhat framed as rhetorical questions, but it is entirely possible that these reasons do play some part in the strength of these peoples, to a greater or lesser extent. But in all cases, these traits have been developed subsequently to the rise of the people who hold them, and as such, should be treated with more skepticism than those that came before.

It might be said further, that the emphasis on ethics positively held is misleading, for the innovations previously discussed, the civilisation build by strengthening positive ethics, and the subsequent material gains made, can offset the need for any sensible or unified ethics in general. A persistent classical critique of their contemporaries is one of lapsed duties, often instead of replaced duties. The men of Greece and Rome being too weak, apathetic, or distracted to preserve the old virtues. Or likewise the later writers under Abbasid rule, and all the steppe nomads that ‘went native’ or ‘went soft’ in the face of all their conquered wealth. Yet still, often these civilisations stayed strong, long after this degeneration had been reported. Many even grew further, as in the case of Greece and Rome. The reasons for this will be multifaceted: based on chance, leadership, and opportunity presented by their neighbours in no small part, and as such, having been raised to such a high material point, that they no longer need the discipline of their people, the degradation can remain unseen by those in a position to see it undone. Or perhaps, as was the case with the man known to history as Augustus; even if the problem is seen by those in a position to try to stem the degradation - if the people themselves do not perceive the necessity, or it has already developed in a positively held ethic, then attempts to reverse it will end poorly.

It must be added, on the topic of ethics, that there may exist two other kinds: one which is only strengthening after civilisation has begun to develop, and another which is weakening once civilisation has begun to develop. Unless the risk of crisis and collapse can be removed entirely, possessing these latter two ethics will ensure that any subsequent downturn is made significantly more disastrous. The bronze age collapse would appear to be one of the ultimate culminations of these factors, because the collapse was so complete. However for this same reason, it is difficult to identify exactly what culturally lead to the collapse, but the fact that this took place in so much more of a complete fashion than the many other governmental/civilisational collapses which we have seen throughout history does suggest that cultural factors were significantly at fault. Perhaps the lack of centralisation and unity in the region for the subsequent millennia was a reaction to the stifling centralisation of that period, perhaps too the movement away from warrior aristocracies, generally but not universally. Although these are significant for the course of later history, these are relatively small alongside the deeper perspective elements, such as: the place of these peoples in the universe, their obligations, what constitutes the “people”, who are their betters, lessers, and equals, and why? So let us consider these matters in ourselves likewise - not merely in terms of what is ‘true’ according to our metaphysical and epistemological systems of choice, but also (in as much as possible) in terms of what brought our ancestors to the civilisation we have today, and thus what we may need to fall back on, should we find ourselves in their position.