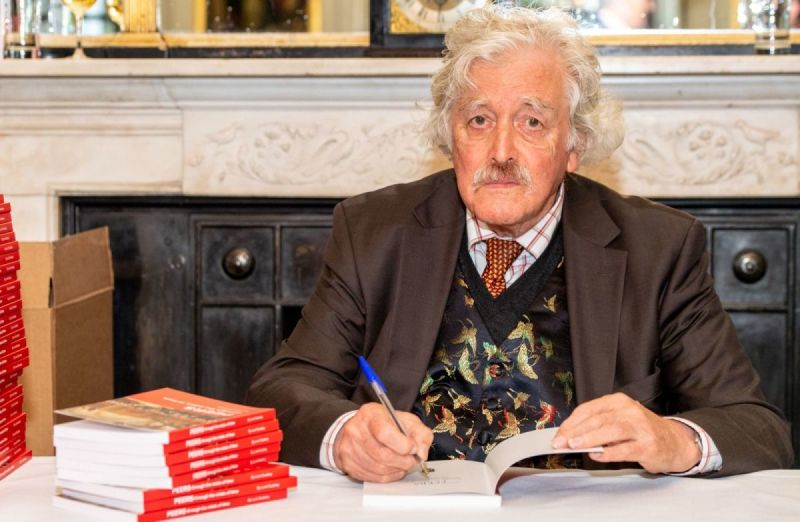

Lord Sudeley's Eulogy of Sir Roger Scruton.

by Committee

Any appreciation of Sir Roger Scruton must be undertaken with diffidence owing to the astonishing size of his oeuvre and the extraordinary extent of his versatility. Truly he was a polymath. On gaining a scholarship to Jesus College, Cambridge, he switched from the natural sciences in order to become our foremost Conservative philosopher. Yet, aside from philosophy, his range of intellectual achievement was really wide. A successful student of law which he never practised, Scruton was also a wine critic for the New Statesman, novelist, and author of a charming book on hunting. And in the realm of aesthetics his first book, Art and Imagination, formed the basis of his subsequent criticism of modern architecture and studies of music where he wrote an opera Violet about the harpsichordist Violet Gordeon Woodhouse which was performed at the Guildhall School of Music.

Furthermore, Scruton must be praised for his magnificent courage in the 1980s, when he helped to establish underground networks in the Communist countries of Eastern Europe for knowledge-starved students defying the secret police. Before being arrested and expelled Scruton himself taught philosophy in Prague, where Havel, later first President of the Czech Republic, became his student. After the fall of Communism, Havel showed ample sympathy for the dispossessed Czech aristocracy, about which I learnt much when I used to stay in the Czech Republic with Vladimir Reisky. After the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968, Reisky, proud descendant of Poland's last and best king Stanislav Poniatowski, emigrated to become a Professor of Political Science in the University of Virginia and a friend of Kissinger; and after the disintegration of Communism he was able to persuade President Havel to restore to him not just his modest Baroque castle of Vilemov but also his family's forestry to support it. If Reisky was of the petite noblesse, his recovery of Vilemov became the fore-runner for the restoration of the properties of various greater members of the Czech aristocracy. It was a miracle. At the same time under Havel's Presidency Scruton was able to establish a consultancy firm needed to make contact between Havel's newly formed government and western businesses.

How did Scruton become a Conservative? Strangely, I believe there was first of all his father Jack Scruton, who may have been a primary school teacher and trade unionist and a hater of the upper classes, yet in his own way was deeply conservative in his love for the English countryside. Many obituaries tell of how Scruton was converted to Conservatism in 1968 by witnessing the student riots in France. Less spoken of was the influence upon him of Peterhouse, Cambridge, delightfully caricatured by Tom Sharpe in his novel Porterhouse Blues, and where Scruton was a Research Fellow from 1969-71. When Hugh Trevor-Roper, Lord Dacre of Glanton, was elected to become Master of Peterhouse, one of the Fellows, the mediaeval economic historian E.M.Postan, said what silly old fools the other Fellows were, in believing they had secured a sound Tory to find they had landed themselves with an eighteenth century Whig. Dacre one day complained to me that if ever he was to understand the College to which he had been elected Master and yet of which he did not really approve, it would be to say that the recovery of high Tory roots had to be a different matter to the inheritance of them. A previous Master, Herbert Butterfield, was indeed born of the humblest Methodist origins in Yorkshire; yet his book The Whig Interpretation of History explains so well everything which is wrong with that interpretation. Amongst the later Fellows of Peterhouse under Butterfield's spell Scruton was chiefly influenced by Maurice Cowling; and Monsignor Gilbey's conversion to Catholicism of the architectural historian David Watkin gave to Watkin the assurance of roots which he so badly needed. Thereafter Watkin used always to march vigorously in the right direction.

What sort of good Tory was Scruton, when Thatcher was indifferent to his kind of political philosophy? An important ingredient of their differences must have been Scruton's mistrust of the Free Market, which, he believed, should be subordinated to the social order. In her commitment to laissez-faire economics Thatcher was really a Manchester Liberal, to follow on from the many Liberals of that ilk, who, in 1886, and under the leadership of Joseph Chamberlain, left the Whig Party over the issue of Irish Home Rule to become cuckoos in the Tory nest, transforming its thinking on economics from within. The Tories became the bankers' party when previously that had been a Whig prerogative. Unlike Thatcher, Scruton was aligned to the pre-1886 Jacobite Toryism so well explained by Sir John Biggs-Davison in his Tory Lives.

Scruton owed much to Burke. Once he said that the role of a Conservative thinker is to re-assure people that their prejudices are true. For Burke prejudice was the bank and capital of ages and of nations. A good definition of prejudice would be to say that it provides a pre-judgement of events on the basis of past experience, which Burke identified with the wisdom of our ancestors. At the same time Scruton liked to stress the truth of Burke's adage that tradition without the means of change is without the means of conservation. In just the same kind of way, however, as the House of Lords evolved until Labour tampered with its hereditary composition, such change must be achieved on a practical, or prescriptive, basis to meet a particular need at a particular time. Burke would never have approved of Labour's eviction of the hereditaries from the House of Lords on the abstract and highly doctrinnaire grounds of a belief in the superiority of the elective over the hereditary principle of government.

Owing to his right wing views Scruton had a big fall out with academia, where he assessed that the Left has become the Establishment. He said his academic career was ended by his editorship of the Salisbury Review from 1982-2001; and just previously to that, in his book The Meaning of Conservatism which was published in 1980, he remarked upon the contagion of democracy. I am proud of introducing Scruton to David Levy, the Editor of the Monday Club's journal Monday World, so that Levy could become an editor of the Salisbury Review.

Levy was gifted interpreter of the political thought of Charles Maurras, leader of Action Francaise, to whom democracy was not a clean word. Both De Tocqueville and John Stuart Mill warned of how dangerous and harmful our present democratic system of majority voting may be towards minority interests, of which significant examples are foxhunting, to which Scruton was addicted, and the countryside to which his father was devoted and the hounds run over. Under Maurras's system of Mediaeval Corporativism minority interests are better protected. The body politic is made up of the various powers and liberties of the land, and whenever they may happen to conflict a hereditary monarch is there to arbitrate.

This is my personal tribute to Sir Rolger Scruton whose death is such a great and sad loss to us. Let me thank a member of the Traditional Britain Group from Australia, Colin Black, for the loan of his dossier of other obituaries which has helped me to put together everything which I have wished to say.