In Defence of Reactionaries

by J MW

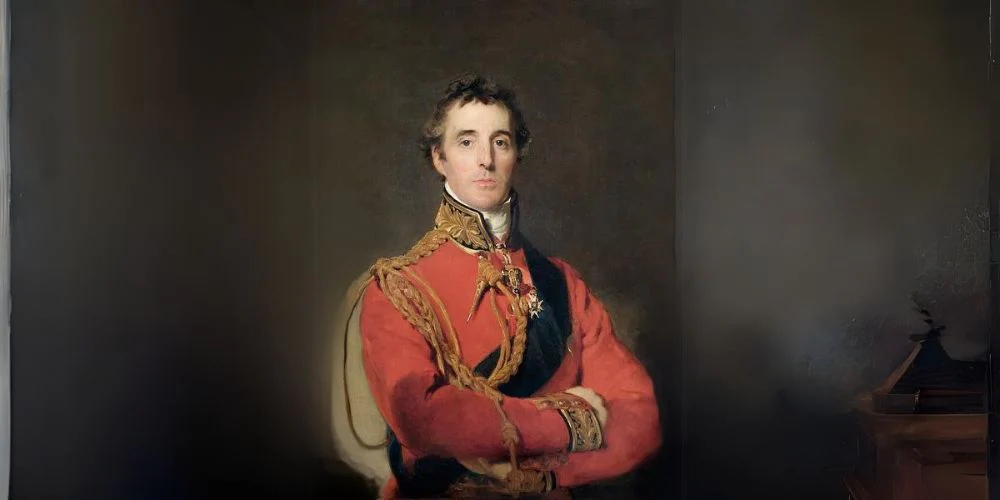

On November 2nd, 1830, Arthur Wellesley, Duke of Wellington, delivered the King’s Speech to the House of Lords. He was answered by Earl Grey, whose attack on the proposed measures closed with a few generalized remarks in favor of a moderate reform of Parliament. Wellington decided that this was an opportunity to make his own position on the issue clear. He declared that he had never heard of any measure of reform which satisfied him to any degree. The system of representation could not be improved. He was fully convinced that the country possessed a legislature which answered the purposes of such bodies better than any in other countries or at other times.

The speech was received in silence by his own side. Taken aback, Wellington asked his neighbor, Lord Aberdeen, ‘I haven’t said too much, have I?’ ‘You’ll hear of it’ was the reported answer. As he left the chamber, Aberdeen was asked what Wellington had said ‘He said were were going out of office’, quipped the future Prime Minister. A fortnight later Wellington’s government collapsed, to the unconcealed relief of some ministers. Aberdeen was more prophetic than the probably imagined; admirers of Wellington are still ‘hearing of it’ today. Indeed, his whole career as a general, a politician, and later as a national institution has been summed up by his opponents by one word: ‘reactionary’.

Two statements from Sir Herbert Butterfield’s The Whig Interpretation of History provided the original excuse for this article. He claims that in general historical works especially, ‘much greater ingenuity and a much higher imaginative endeavor have been brought into play upon the Whigs, progressives and even revolutionaries of the past, than have been exercised upon the elucidation of Tories and conservatives and reactionaries. The Whig historian withdraws the effort in the case of the men who are most in need of it’.

This reads like a challenge to historians to espouse the cause of reactionaries in the same manner that Whig historians have championed their opponents. But earlier in his essay Butterfield had seemed to rule such an exercise out of order; ‘it cannot be said that all faults of bias can be balanced by work that is deliberately written with the opposite bias; for we do not gain true history by merely adding the speech of the prosecutions to the speech for the defence’.

The only pity is that the Whig prosecutors have already expounded their position. The original wrong is theirs, but those who retaliate seem likely to be convicted for it. Reactionary historians, indeed, will probably fare no better than those they wish to defend. In view of this, the most promising approach is probably not to defend reactionaries directly, but to undertake the prosecution of the prosecutors.

To call someone a reactionary is, in fact, to establish his guilt at the outset. It is possibly the most value-laden term available to historians. Other political names which were originally insults such as ‘Tory’ and ‘Whig’, have become sterilized over time, as the bandits and outlaws who inspired the names have faded from memory. But the word ‘reactionary’ will never lose currency as an insult until a time when the belief in inevitable progress (without which it is meaningless) is laid to rest. The word seems to be lost without the accompanying adjective ‘hidebound’. The reactionary must be either ‘stupid’, ‘unrealistic’, or both, while ‘radical’ connotes at least a highly-developed critical faculty.

There is a romantic ambience around the word radical, which makes the opponents of the radical Thatcherites deny the word to them. The radical might be misguided, but we are directed to believe that his errors fall on the side of decency. Failure for the radical ensures the consolatory phrase ‘ahead of his time’ in the hagiographies, the blood of his opponents must have been infected by the reactionary taint. The failed reactionary is passed over in embarrassed silence by those who might have supported him; his foes need only pronounce the name of his kind to call forth the ritual curses.

It seems that the reactionaries of history are damned far beyond all hope of redemption. However, his may turn out to be a pyrrhic achievement on the part of Whigs and Marxists. ‘Reactionary’ is a term of abuse with a limitless range of possible targets, and as such is a barbed shaft which must always fall hurtles. It is intended to wound and not to describe, and as such it merely reveals the lack of effective weapons available to anti-conservative historians. If this claim can be sustained, the word should be abandoned by any scholar who prefers solid judgements to rhetoric in descriptions of the past.

The first reactionary, if Milton is to be believed, was Adam. The radical Eve wished to escape the bounds imposed upon her by God: instead of marvelling at her incisive and penetrating blueprint for human progress, Adam was perverse enough to be displeased. Like all reactionaries, however, he found that the tide of events had moved beyond his control, and he learned to live with the results of Eve’s activism. In more modern times one might point to those who crushed the Jacobins in late Eighteenth century France as more accessible subjects for scrutiny. These were a mostly collection of royalists, Dantonists, Girondins, frightened Jacobins and men who had always preferred pennies to principles. They first denounced and then executed Robespierre, ruling France from the ninth of Thermidor 1794 to the coup debate of Napoleon in 1798. One might say that these men ‘reacted’ against the Red Terror, which was judged unnecessary once the greatest danger to the nation had passed, and internal enemies no longer needed to be identified or invented.

The second reaction in France took place after the fall of Napoleon in 1815. The first restored Bourbon King, Louis XVIII, was a sensible man who seems to have plumped happily for a fixed abode after years of living out of a traveling-chest. His brother Charles was not wedded to tranquility, however, being the epitome of those whom Talleyrand congratulated on having learned nothing and forgotten nothing from the Revolutionary experience. He wanted an active role in government for himself, but his interventions were not felicitous, and the fist sign of trouble in 1830 sent him back into exile.

Detailed studies as Butterfield hinted, tend to put Whig and Marxist historians at an unfair disadvantage since they reveal the true complexity of events. But even the Whiggish outlines reveal that the word ‘reactionary’ can be applied in two different contexts. The first example was the result of a desire to arrest the headlong velocity of change: the second was an attempt to turn the clock back. Those who uphold the use of the word ‘reactionary’ might agree that there is indeed such a dual application. But this merely produces a further problem. In the first example, the reaction was led by liberal republicans, who still identified with the principles of 1789—in so far as they had any principles at all. In the second, the driving force of reaction was provided by conservative monarchists, such as Bonald and de Maistre. If there was any unity of purpose among these assorted reactionaries, the success of the Thermidorian uprising, one supposes, should have obviated the need for a second. But there was no such unity. The terrible truth seems to be that since the first reaction was a liberal republican reaction, and the second a product of conservative monarchism, then the word ‘reaction’ is entirely superfluous and lends nothing to an historical understanding of these events.

However, the appearance of Napoleon Bonaparte in the years that separated these coups, might alter the picture. For the Whig historian, this man presents a considerate difficulty. Although he retained some of the institutions created by the Revolution, he restored the spiritual authority of the Pope, his legion d’honneur smacks of the old aristocracy, he repressed the Jacobins as fiercely as his predecessors, and he restored the monarchy under a new name (which had provocative reactionary implications). In short, if there was a reactionary in this period, it was Napoleon; and yet history knows him as the supplanter of a reactionary regime, who in turn was toppled by a reaction. It is perhaps fortunate that he himself is rarely called a reactionary.

How might the word reactionary be properly applied? Firstly, it might be said that a reactionary resists change. This seems to fit nicely with the idea that all reactionaries are conservatives. But those who resist change in non-conservative regimes are not themselves conservatives. They resist change because their liberal, socialist or fascist beliefs are satisfied by the present ruling party or clique. Very few regimes, however, resist all change during their days of power. While a government is rejecting changes in the electoral system, for instance, it might be changing the laws of dog-ownership. Such a government would be both reactionary and radical at the same time. Thus, non-conservatives may resist change, and governments may promote changes in some areas while rejecting it in others. The Whig will concentrate on electoral factors, the Marxists on social and economic policies. We must discard mere resistance to change as a defining characteristic of reaction.

Another possibility is that reactionaries are those who wish to turn the clock back. This is perhaps the most familiar usage of the word, but it can easily be exposed as indefensible. The supporters of every overthrown regime, whatever its nature, would become reactionaries at the moment that power changed hands. In the seventeenth century virtually the only Englishman to avoid the taint of reaction would thus have been the Vicar of Bray.

Surely this is taking paradox too far. Does not everyone know that the Thatcher government was the most reactionary Britain has ever had? Its ideals, after all, were derived from the Manchester School of the previous century, if not from Adam Smith himself. Perhaps this should be the new definition of a reactionary—one wh is inspired to political activism by a vision of the distant past. Such slogans as ‘Victorian morality’, therefore, surely demonstrate the reactionary nature of Thatcherism?

Unfortunately this line is just as untenable as the others. Some opponents of Mrs. Thatcher are inspired by Marxist doctrines which are equally superannuated. When does a vision of the past, or adherence to a doctrine, become the hallmark of a reactionary? What is the shelf-life of a political principle? The monarchists of 1815 dreamed of a time only a quarter-century past, and they are regarded as the most besotted reactionaries of the lot. On this theory, if a government of the strongest left-wing inclinations were toppled by force, the longer its supporters were repressed, the more reactionary they would become.

The common problem for those who believe that a reactionary is one who stands out against the trend of history is not simply that such trends differ through the eyes of different beholders, but also that the label is generally used only when the ‘reactionary’ is successful. Hence, the supporters of the Bourbon restoration are usually called ‘emigrants’ or ‘Royalists’ until the moment when they took power. The triumphs of ‘reaction’ have not been mysterious jolts in the otherwise smoothly-running conveyor-belt of time; in hindsight, their successes look quite as ‘inevitable’ as their setbacks. A satisfactory theory of historical development would have to include these temporary blips as well as the glorious advances. Paradoxically, therefore, those who tar their opponents with the reactionary brush and thereby draw attention to the occasional hiccups of history undermine their own theories as they do so.

A final and more sympathetic possibility can be derived from Newtonian physics. It might be claimed that reactionaries perform a valuable function in maintaining the equilibrium of any political system. If there was no reaction to every action, then state stability would be destroyed. At least the approach implies even-handedness between the two sides. But it is still unsatisfactory. First, implies that the reaction is produced by the desire for reform. The commonness of this mistake does not make it any more correct. Writers who have opposed reform, like Burke in his Reflections, have not merely invented some excuses for their opposition because they felt their position under threat; rather, the situation called for the urgent expression of views which they already held. Indeed, if there is a struggle between action and reaction, it is most often the advocates of change who are reacting to the beliefs and practices of the status quo.

Secondly, human thoughts and actions are not ruled by the laws of physics. Not every demand for change provokes an opposing force. Reforms can be accepted without demur, and sometimes habitual opponents of change (such as Wellington himself) advocate far-reaching measures themselves. Coleridge’s forces of ‘permanence’ and ‘progression’, or the Hegelian dialectic are obviously profound insights into the movement of ideas which are not completely divorced from the cruder Newtonian theory. These ideas (significantly enough the products of conservative thought) lie outside our present scope. It is quite enough to note that they suffer from an assumption that history is moving in a certain direction, which we criticised earlier wand which tells equally against the Newtonian position.

A few words in praise of reactionaries might be attempted in conclusion. A good starting-point is provided by historians who habitually use the term. It is intended as an insult, but there is something oddly complimentary about it too. There is an implication of hidden power ‘the forces of reaction’ being a common expression. There is another way in which the weapon might be turned against those who wield it. Any attempt to prejudice the reader against certain historical figures before the evidence is produced implies deep insecurity. If the reactionaries were permitted a fair trial, perhaps, readers might reach unsound verdicts. The best thing, therefore, is to denounce them as guilty from the outset.

Not all those who have been called reactionaries can be appraised without overt disapproval. I would not wish to claim that all such value judgments should be entirely expunged from the history books, nor that since reactionaries are condemned to a man, they should all now be rehabilitated simply because a word has been found to be meaningless. It would seem, however, that if the misdeeds of reactionaries were so heinous, it would be unnecessary to add any opprobrious epithets to an account of their activities. Perhaps the safest claim that we might put forward is that those figures who have been tarred as reactionaries deserve to be re-examined free from such a prejudicial labelling at the outset.

A few words might also be said on behalf of the reactionary Iron Duke. On 2nd November 1830 he committed a serious strategic blunder. He alienated both wings of his party at a time when tact was required to keep his troops together. Had he restrained his genuine enthusiasm on that day, history may have treated him differently. The Whigs wanted limited reform, in the main because they felt sure that it would bring electoral success for them; at least until the bloodless French Revolution of 1830, they were very tentative advocates. Wellington did not want reform because he felt that the Constitution could not be improved. It is not an easy task to prove that he was wrong in this belief. Clearly he was mistaken in his claim that reform had no support, but parliamentary hyperbole was not Wellington’s invention, and there had been demands for an extension of the franchise before, which had been resisted with little dicculty. Overall, one might suggest that without Wellington Parliamentary reform would not have occurred in 2832, and the Whigs should remember the Duke in every prayer. Those who regard the Reform Act as a mistake might admire him for his determination to serve his country to the best of his ability and his willingness to compromise when national tranquillity required. Unfortunately, Wellington is still the subject of either derision or clumsy apologetics which undermine him still more. It is sixty years since Butterfield wrote his attack on biased history, but it seems as though the case for the defence has still to be made.

Mark Garnett was Lecturer in Politics at the University of Durham.