The Heart Of Conservatism Is Community

by TBG

The Heart Of Conservatism Is Community by A.B.

Across the mainstream right, a dominant narrative has emerged that it is the conservative position to defend the "sovereignty of the individual" and individualism itself from attacks from "collectivists", a broadly defined term for anyone who disagrees with that atomistic and individualistic view of humanity and society perhaps best encapsulated by Mrs. Thatcher's assertion that "there is no such thing as society." The truth, however, is that this has never been the true conservative position; it is the classical liberal position.

Indeed, the purveyors of this notion, that it is the duty of the right to defend individualism, and that individualism is an essential predicate of Western civilisation, from F.A. Hayek¹ to Jordan B. Peterson, ² reject the label of "conservative" to describe themselves and their ideologies, whilst identifying themselves instead as classical liberals.

Their individualistic worldview stems from, as I seek to demonstrate (drawing from great communitarian conservative thinkers from throughout the history of Western thought) in this piece, a fundamentally flawed notion of how human identities, communities and states evolve and form.

Firstly, the atomistic worldview misunderstands the development of human self-consciousness, and how this leads to the development of collective identities. The classical liberals who are often mistaken for conservatives assume that humans are born as free individuals who can achieve self-consciousness by their lonesome, and for this reason, as Peterson so often puts it, the individual is "sovereign", i.e. paramount, with the community being subordinate to it, and something which the individual freely chooses to be part of, and therefore, the role of the state is merely to facilitate the pursuits of the individual.

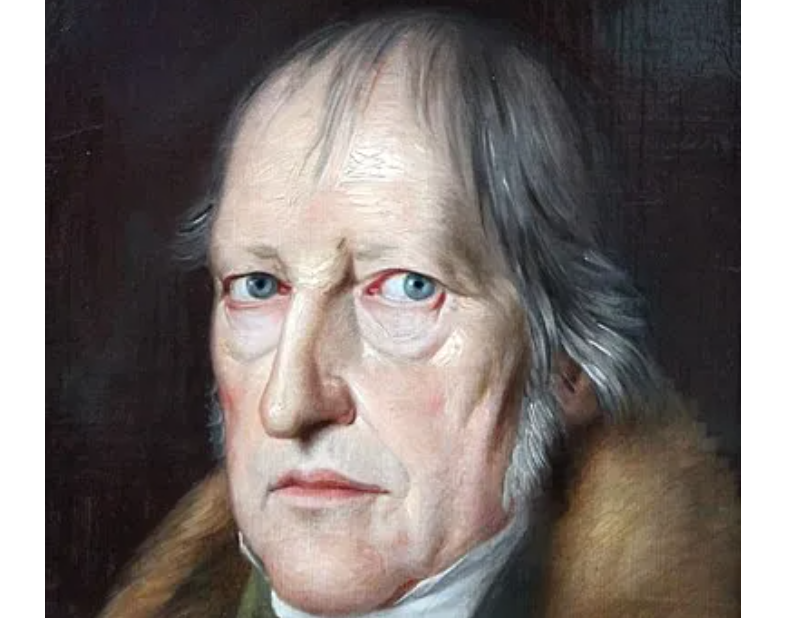

This is a mistaken worldview, as we can discover by looking to the great 19th-century German idealist philosopher and conservative political theorist Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel. In his brilliant work, the Phenomenology of Spirit, ³ Hegel demonstrates that the development of our own self-consciousness depends on recognition from others.

Who we understand ourselves to be comes not from within, or from obtaining recognition from others by force and subjugation (as Hegel outlines in his famous dialectic of the lord and the bondsman), it comes instead from recognition from another self-consciousness who we ourselves recognize as being worthy of granting us said recognition, and vice versa, or as Hegel puts it in ¶184 of the Phenomenology, the two incarnations of self-consciousness must "recognize themselves as mutually recognizing one another."⁴

This becomes evident when we consider ourselves. Our knowledge of our place in the world comes directly from and is validated by acknowledgement by others. Without passing this test of external validation, we cannot know who we truly are. This demonstrates that the classical liberal view of the individual is based, first and foremost, on a fundamental misunderstanding of how our very sense of self develops, and misses the fact that our sense and knowledge of ourselves as free individuals depends on our being recognized as such by other free individuals. It is clear, then, that this is the basis upon which we form collective and cooperative units, whether that is the family, the local community, the national community or any other such collective framework, or as the intellectual forefather of conservatism, Edmund Burke famously described them, any "little platoon to which we belong in society."⁵

After it is established that two incarnations of self-consciousness are dependent on one another for their sense of self, it is clear that as more and more individuals engage in the process of mutual recognition, and thus recognition itself becomes a web, a complex pattern of individuals, some of whom we may have never met, but who share something higher, a collective identity or collective consciousness. This is what Hegel termed Spirit or Geist in German, illustrating that communities develop organically. This Spirit manifests itself in culture, art, and other mediums. The highest community which is developed via this organic process is the state, which is, as Hegel outlined in his Elements of the Philosophy of Right, the dialectical union of the particular desires of the individuals within society with the interests and concerns of the whole, and in which ethics are universalized.

This is again where we see the collapse of the classical liberal worldview. Classical liberals believe the state must be constrained to give way to the forces of the market and the initiative of the sovereign individual. Hegel, however, teaches us that it is only through the state that we can achieve true political freedom, or freedom in its highest form. Liberals of all stripes proceed from the contractarian view of the state as elucidated by Thomas Hobbes and John Locke, among others that the state is an imagined social contract between the government and the governed, by which the governed concede their natural freedoms which they enjoy in the state of nature in exchange for security. This begs the question of whether the freedom we enjoyed in the state of nature is truly, fully freedom, and Hegel shows us that it is not. In the Philosophy of Right, Hegel describes the "freedom" which we enjoy in the state of nature as "natural freedom", but it is not truly freedom as it puts all individuals at the mercy of one another, meaning that people are governed by the law of the jungle, not the laws created by man. For Hegel, true freedom can only be found through ethical living, or Sittlichkeit in German, in which we humans establish our own ethical codes of conduct and thus become free, by living according to our own laws and becoming self-determining, as opposed to living according to the forces of nature and being consistently subjugated by others in an eternal struggle.

This ethical living ultimately becomes universalized in the state, as the rule of law binds all together in a formalized ethical framework. As Hegel puts it: "The state in and by itself is the ethical whole, the actualisation of freedom."⁶ This, as we can see, departs from the liberal idea of freedom as simply the unrestrained ability to make choices, and instead harks back to the ancient Greek idea of freedom as the self-mastery which Plato so beautifully illustrated in his allegory of the chariot, meaning that we transcend the law of conflict which nature imposed on us by formulating an ethical society based on norms which are ultimately universalized in a state governed by laws, all of which were of our own conscious creation. It also marks a return to Aristotle's idea of man as "naturally a political animal”, ⁷ suggesting that politics does not emerge as an unnatural, oppressive force which is a necessary evil for the sake of security, but that it organically develops according to our nature in order to actualize our own freedom. Liberal contractarians put the cart before the horse by asserting that in the formation of the state we gave up much of our pre-existing freedom, which in reality, however, was never truly freedom itself - it is only in ethics and ultimately the state and its laws that we achieve true freedom.

To conclude, the liberal worldview of the individual as an entirely independent, sovereign and self-sustaining entity is left wanting by the fact that our very sense of individuality itself is dependent on recognition from others and our recognition of them. As is the liberal worldview of the state as an inherently oppressive force which must be kept limited and clipped at the wings at all costs. It is only in the state that we achieve true freedom from the law of the jungle, with it instead being sublated by the laws of man.

It is lamentable that these false interpretations of human nature and of the reality of the state, which authentic conservatives spent centuries opposing and arguing against, have, along with market fundamentalist policies informed by said interpretations, been adopted by vast swathes of the self-identified conservative movement. It ought to be the goal of all self-respecting conservatives to defend the value of the community, the "little platoon(s)" which Burke held so dear, for as Sir Roger Scruton so eloquently explained: "We are not born free, nor do we come into this world with a self-identity and autonomy of our own. We achieve those things, through the conflict and cooperation that weave us into the social fabric."⁸

- Hayek, Friedrich A. (2011). "Why I am not a Conservative". The Constitution of Liberty (Definitive ed.). The University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-31539-3. #

- Robertson, Derek (16 June 2018). "Why the 'classical liberal' is making a comeback". Politico Magazine. #

- Hegel, Georg Wilhelm Friedrich (2018). Terry Pinkard (ed.). The Phenomenology of Spirit, ¶178-196. Translated by Pinkard, Terry. Cambridge University Press. #

- Hegel, Georg Wilhelm Friedrich (2018). Terry Pinkard (ed.). The Phenomenology of Spirit, ¶184. Translated by Pinkard, Terry. Cambridge University Press.

- Burke, Edmund; Turner, Frank M. (2003) Reflections on the Revolution in France (Rethinking the Western Tradition), 40. Yale University Press. ISBN 0300099797, 978-0300099799. Audio, text.

- Hegel, Georg Wilhelm Friedrich (2008). Knox, T. M. (ed.). Outlines of the Philosophy of Right, ¶258. Oxford University Press. 9780192806109, 0192806106. #

- Jowett, Benjamin & Aristotle, Benjamin (1887). The Politics of Aristotle, 1253a. Oxford,: Clarendon Press. Edited by William Lambert Newman. 0405048483, 0198141114, 0195003063, 9780195003062, 0405048513. #

- Scruton, Roger (21 December 2015). "Conservatism and the Conservatory". National Review. #