History and Decadence: Spengler's Cultural Pessimism Today

by The Editor

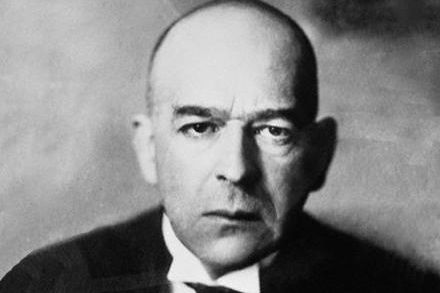

Dr. Tomislav Sunic expertly examines the Weltanschauung of Oswald Spengler and its importance for today's times.

by Tomislav Sunic

Oswald Spengler (1880-1936) exerted considerable influence on European conservatism before the Second World War. Although his popularity waned somewhat after the war, his analyses, in the light of the disturbing conditions in the modern polity, again seem to be gaining in popularity. Recent literature dealing with gloomy postmodernist themes suggests that Spengler's prophecies of decadence may now be finding supporters on both sides of the political spectrum. The alienating nature of modern technology and the social and moral decay of large cities today lends new credence to Spengler's vision of the impending collapse of the West. In America and Europe an increasing number of authors perceive in the liberal permissive state a harbinger of 'soft' totalitarianism that my lead decisively to social entropy and conclude in the advent of 'hard' totalitarianism'.

Spengler wrote his major work The Decline of the West (Der Untergang des Abendlandes) against the background of the anticipated German victory in World War I. When the war ended disastrously for the Germans, his predictions that Germany, together with the rest of Europe, was bent for irreversible decline gained a renewed sense of urgency for scores of cultural pessimists. World War I must have deeply shaken the quasi-religious optimism of those who had earlier prophesied that technological intentions and international economic linkages would pave the way for peace and prosperity. Moreover, the war proved that technological inventions could turn out to be a perfect tool for man's alienation and, eventually, his physical annihilation. Inadvertently, while attempting to interpret the cycles of world history, Spengler probably best succeeded in spreading the spirits of cultural despair to his own as well as future generations.

Like Giambattista Vico, who two centuries earlier developed his thesis about the rise and decline of culture, Spengler tried to project a pattern of cultural growth and cultural decay in a certain scientific form: 'the morphology of history'--as he himself and others dub his work--although the term 'biology' seems more appropriate considering Spengler's inclination to view cultures and living organic entities, alternately afflicted with disease and plague or showing signs of vigorous life. Undoubtedly, the organic conception of history was, to a great extent, inspired by the popularity of scientific and pseudoscientific literature, which, in the early twentieth century began to focus attention on racial and genetic paradigms in order to explain the patterns of social decay. Spengler, however, prudently avoids racial determinism in his description of decadence, although his exaltation of historical determinism in his description often brings him close to Marx--albeit in a reversed and hopelessly pessimistic direction. In contrast to many egalitarian thinkers, Spengler's elitism and organicism conceived of human species as of different and opposing peoples, each experiencing its own growth and death, and each struggling for survival. 'Mankind', writes Spengler, should be viewed as either a 'zoological concept or an empty word'. If ever this phantom of mankind vanishes from the circulation of historical forms, 'we shall ten notice an astounding affluence of genuine forms.. Apparently, by form, (Gestalt), Spengler means the resurrection of the classical notion of the nation-state, which, in the early twentieth century, came under fire from the advocates of the globalist and universalist polity. Spengler must be credited, however, with pointing out that the frequently used concept 'world history', in reality encompasses an impressive array of diverse and opposing cultures without common denominator; each culture displays its own forms, pursues its own passions, and grapples with its own life or death. 'There are blossoming and ageing cultures', writes Spengler, 'peoples, languages, truths, gods and landscapes, just as there are young and old oak trees, pines, flowers, boughs, and peta;s--but there is no ageing mankind.'. For Spengler, cultures seem to be growing in sublime futility, with some approaching terminal illness, and others still displaying vigorous signs of life. Before culture emerged, man was an ahistorical creature; but he becomes again ahistorical and, one might add, even hostile to history: 'as soon as some civilisation has developed its full and final form, thus putting a stop to the living development of culture." (2:58; 2:38).

Spengler was convinced, however, that the dynamics of decadence could be fairly well predicted, provided that exact historical data were available. Just as the biology of human beings generates a well-defined life span, resulting ultimately in biological death, so does each culture possess its own ageing 'data', normally lasting no longer than a thousand years-- a period, separating its spring from its eventual historical antithesis, the winter, of civilisation. The estimate of a thousand years before the decline of culture sets in corresponds to Spengler's certitude that, after that period, each society has to face self-destruction. For example, after the fall of Rome, the rebirth of European culture started andes in the ninth century with the Carolingian dynasty. After the painful process of growth, self-assertiveness, and maturation, one thousand years later, in the twentieth century, cultural life in Europe is coming to its definite historical close.

As Spengler and his contemporary successors see it, Western culture now has transformed itself into a decadent civilisation fraught with an advanced form of social, moral and political decay. The First signs of this decay appeared shortly after the Industrial Revolution, when the machine began to replace man, when feelings gave way to ratio. Ever since that ominous event, new forms of social and political conduct have been surfacing in the West--marked by a widespread obsession with endless economic growth and irreversible human betterment--fueled by the belief that the burden of history can finally be removed. The new plutocratic elites, that have now replaced organic aristocracy, have imposed material gain as the only principle worth pursuing, reducing the entire human interaction to an immense economic transaction. And since the masses can never be fully satisfied, argues Spengler, it is understandable that they will seek change in their existing polities even if change may spell the loss of liberty. One might add that this craving for economic affluence will be translated into an incessant decline of the sense of public responsibility and an emerging sense of uprootedness and social anomie, which will ultimately and inevitably lead to the advent of totalitarianism. It would appear, therefore, that the process of decadence can be forestalled, ironically, only by resorting to salutary hard-line regimes.

Using Spengler's apocalyptic predictions, one is tempted to draw a parallel with the modern Western polity, which likewise seems to be undergoing the period of decay and decadence. John Lukacs, who bears the unmistakable imprint of Spenglerian pessimism, views the permissive nature of modern liberal society, as embodied in America, as the first step toward social disintegration. Like Spengler, Lukacs asserts that excessive individualism and rampant materialism increasingly paralyse and render obsolete the sense of civic responsibility. One should probably agree with Lukacs that neither the lifting of censorship, nor the increasing unpopularity of traditional value, nor the curtailing of state authority in contemporary liberal states, seems to have led to a more peaceful environment; instead, a growing sense of despair seems to have triggered a form of neo-barbarism and social vulgarity. 'Already richness and poverty, elegance and sleaziness, sophistication and savagery live together more and more,' writes Lukacs. Indeed, who could have predicted that a society capable of launching rockets to the moon or curing diseases that once ravaged the world could also become a civilisation plagued by social atomisation, crime, and an addiction to escapism? With his apocalyptic predictions, Lukacs similar to Spengler, writes: 'This most crowded of streets of the greatest civilisation; this is now the hellhole of the world.'

Interestingly, neither Spengler nor Lukacs nor other cultural pessimists seems to pay much attention to the obsessive appetite for equality, which seems to play, as several contemporary authors point out, an important role in decadence and the resulting sense of cultural despair. One is inclined to think that the process of decadence in the contemporary West is the result of egalitarian doctrines that promise much but deliver little, creating thus an economic-minded and rootless citizens. Moreover, elevated to the status of modern secular religions, egalitarianism and economism inevitably follow their own dynamics of growth, which is likely conclude, as Claude Polin notes, in the 'terror of all against all' and the ugly resurgence of democratic totalitarianism. Polin writes: 'Undifferentiated man is par excellence a quantitative man; a man who accidentally differs from his neighbours by the quantity of economic goods in his possession; a man subject to statistics; a man who spontaneously reacts in accordance to statistics'. Conceivably, liberal society, if it ever gets gripped by economic duress and hit by vanishing opportunities, will have no option but to tame and harness the restless masses in a Spenglerian 'muscled regime'.

Spengler and other cultural pessimists seem to be right in pointing out that democratic forms of polity, in their final stage, will be marred by moral and social convulsions, political scandals, and corruption on all social levels. On top of it, as Spengler predicts, the cult of money will reign supreme, because 'through money democracy destroys itself, after money has destroyed the spirit' (2: p.582; 2: p.464). Judging by the modern development of capitalism, Spengler cannot be accused of far-fetched assumptions. This economic civilisation founders on a major contradiction: on the one hand its religion of human rights extends its beneficiary legal tenets to everyone, reassuring every individual of the legitimacy of his earthly appetites; on the other, this same egalitarian civilisation fosters a model of economic Darwinism, ruthlessly trampling under its feet those whose interests do not lie in the economic arena.

The next step, as Spengler suggest, will be the transition from democracy to salutary Caesarism; substitution of the tyranny of the few for the tyranny of many. The neo-Hobbesian, neo-barbaric state is in the making:

Instead of the pyres emerges big silence. The dictatorship of party bosses is backed up by the dictatorship of the press. With money, an attempt is made to lure swarms of readers and entire peoples away from the enemy's attention and bring them under one's own thought control. There, they learn only what they must learn, and a higher will shapes their picture of the world. It is no longer needed--as the baroque princes did--to oblige their subordinates into the armed service. Their minds are whipped up through articles, telegrams, pictures, until they demand weapons and force their leaders to a battle to which these wanted to be forced. (2: p.463)

The fundamental issue, however, which Spengler and many other cultural pessimists do not seem to address, is whether Caesarism or totalitarianism represents the antithetical remedy to decadence or, orator, the most extreme form of decadence? Current literature on totalitarianism seems to focus on the unpleasant side effects of the looted state, the absence of human rights, and the pervasive control of the police. By contrast, if liberal democracy is indeed a highly desirable and the least repressive system of all hitherto known in the West--and if, in addition, this liberal democracy claims to be the best custodian of human dignity--one wonders why it relentlessly causes social uprootedness and cultural despair among an increasing number of people? As Claude Polin notes, chances are that, in the short run, democratic totalitarianism will gain the upper hand since the security to provides is more appealing to the masses than is the vague notion of liberty. One might add that the tempo of democratic process in the West leads eventually to chaotic impasse, which necessitates the imposition of a hard-line regime.

Although Spengler does not provide a satisfying answer to the question of Caesarism vs. decadence, he admits that the decadence of the West needs not signify the collapse of all cultures. Rather it appears that the terminal illness of the West may be a new lease on life for other cultures; the death of Europe may result in a stronger Africa or Asia. Like many other cultural pessimists, Spengler acknowledges that the West has grown old, unwilling to fight, with its political and cultural inventory depleted; consequently, it is obliged to cede the reigns of history to those nations that are less exposed to debilitating pacifism and the self-flagellating feelings of guilt that, so to speak, have become the new trademarks of the modern Western citizen. One could imagine a situation where these new virile and victorious nations will barely heed the democratic niceties of their guilt-ridden formser masters, and may likely at some time in the future, impose their own brand of terror that could eclipse the legacy of the European Auschwitz and the Gulag. In view of the turtles vicil and tribal wars all over the decolonized African and Asian continent it seems unlikely that power politics and bellicosity will disappear with the 'Decline of the West'; So far, no proof has been offered that non-European nations can govern more peacefully and generously than their former European masters. 'Pacifism will remain an ideal', Spengler reminds us, 'war a fact. If the white races are resolved never to wage a war again, the coloured will act differently and be rulers of the world'.

In this statement, Spengler clearly indicts the self-hating 'homo Europeanus' who, having become a victim of his bad conscience, naively thinks that his truths and verities must remain irrefutably turned against him. Spengler strongly attacks this Western false sympathy with the deprived ones--a sympathy that Nietzsche once depicted as a twisted form of egoism and slave moral. 'This is the reason,' writes Spengler, why this 'compassion moral', in the day-to day sense 'evolved among us with respect, and sometimes strived for by the thinkers, sometimes longed for, has never been realised' (I: p.449; 1: p.350).

This form of political masochism could be well studied particularly among those contemporary Western egalitarians who, with the decline of socialist temptations, substituted for the archetype of the European exploited worker, the iconography of the starving African. Nowhere does this change in political symbolics seem more apparent than in the current Western drive to export Western forms of civilisation to the antipodes of the world. These Westerners, in the last spasm of a guilt-ridden shame, are probably convinced that their historical repentance might also secure their cultural and political longevity. Spengler was aware of these paralysing attitudes among Europeans, and he remarks that, if a modern European recognises his historical vulnerability, he must start thinking beyond his narrow perspective and develop different attitudes towards different political convictions and verities. What do Parsifal or Prometheus have to do with the average Japanese citizen, asks Spengler? 'This is exactly what is lacking in the Western thinker,' continues Spengler, 'and watch precisely should have never lacked in him; insight into historical relativity of his achievements, which are themselves the manifestation of one and unique, and of only one existence" (1: p.31; 1: p.23). On a somewhat different level, one wonders to what extent the much-vaunted dissemination of universal human rights can become a valuable principle for non-Western peoples if Western universalism often signifies blatant disrespect for all cultural particularities.

Even with their eulogy of universalism, as Serge Latouche has recently noted, Westerners have, nonetheless, secured the most comfortable positions for themselves. Although they have now retreated to the back stage of history, vicariously, through their humanism, they still play the role of the indisputable masters of the non-white-man show. 'The death of the West for itself has not been the end of the West in itself', adds Latouche. One wonders whether such Western attitudes to universalism represent another form of racism, considering the havoc these attitudes have created in traditional Third World communities. Latouche appears correct in remarking that European decadence best manifests itself in its masochistic drive to deny and discard everything that it once stood for, while simultaneously sucking into its orbit of decadence other cultures as well. Yet, although suicidal in its character, the Western message contains mandatory admonishments for all non-European nations. He writes:

The mission of the West is not to exploit the Third World, no to christianise the pagans, nor to dominate by white presence; it is to liberate men (ands seven more so women) from oppression and misery. In order to counter this self-hatred of the anti-imperialist vision, which concludes in red totalitarianism, one is now compelled to dry the tears of white man, and thereby ensure the success of this westernisation of the world. (p.41)

The decadent West exhibits, as Spengler hints, a travestied culture living on its own past in a society of indifferent nations that, having lost their historical consciousness, feel an urge to become blended into a promiscuous 'global polity'. One wonders what would he say today about the massive immigration of non-Europeans to Europe? This immigration has not improved understanding among races, but has caused more racial and ethnic strife that, very likely, signals a series of new conflicts in the future. But Spengler does not deplore the 'devaluation of all values nor the passing of cultures. In fact, to him decadence is a natural process of senility that concludes in civilisation, because civilisation is decadence. Spengler makes a typically German distinction between culture and civilisation, two terms that are, unfortunately, used synonymously in English. For Spengler civilisation is a product of intellect, of completely rationalised intellect; civilisation means uprootedness and, as such, it develops its ultimate form in the modern megapolis that, at the end of its journey, 'doomed, moves to its final self-destruction' (2: p.127; 2: p. 107). The force of the people has been overshadowed by massification; creativity has given way to 'kitsch' art; genius has been subordinated to the terror reason. He writes:

Culture and civilisation. On the one hand the living corpse of a soul and, on the other, its mummy. This is how the West European existence differs from 1800 and after. The life in its richness and normalcy, whose form has grown up and matured from inside out in one mighty course stretching from the adolescent days of Gothics to Goethe and Napoleon--into that old artificial, deracinated life of our large cities, whose forms are created by intellect. Culture and civilisation. The organism born in countryside, that ends up in petrified mechanism (1: p.453; 1: p.353).

In yet another display of determinism, Spengler contends that one cannot escape historical destiny: 'the first inescapable things that confronts man as an unavoidable destiny, which no though can grasp, and no will can change, is a place and time of one's birth: everybody is born into one people, one religion, one social stays, one stretch of time and one culture.' Man is so much constrained by his historical environment that all attempts at changing one's destiny are hopeless. And, therefore, all flowery postulates about the improvement of mankind, all liberal and socialist philosophising about a glorious future regarding the duties of humanity and the essence of ethics, are of no avail. Spengler sees no other avenue of redemption except by declaring himself a fundamental and resolute pessimist:

Mankind appears to me as a zoological quantity. I see no progress, no goal, no avenue for humanity, except in the heads of the Western progress-Philistines...I cannot see a single mind and even less a unity of endeavours, feelings, and understanding in thsese barren masses people. (Selected Essays, p.73-74; 147).

The determinist nature of Spengler's pessimism has been criticised recently by Konrad Lorenzz who, while sharing Spengler's culture of despair, refuses the predetermined linearity of decadence. In his capacity of ethologist and as one of the most articulate neo-Darwinists, Lorenz admits the possibility of an interruption of human phylogenesis--yet also contends that new vistas for cultural development always remain open. 'Nothing is more foreign to the evolutionary epistemologist, as well, to the physician,' writes Lorenz, 'than the doctrine of fatalism.' Still, Lorenz does not hesitate to criticise vehemently decadence in modern mass societies that, in his view, have already given birth to pacified and domesticated specimens, unable to pursue cultural endeavours,. Lorenz would certainly find positive renounce with Spengler himself in writing:

This explains why the pseudodemocratic doctrine that all men are equal, by which is believed that all humans are initially alike and pliable, could be made into a state religion by both the lobbyists for large industry and by the ideologues of communism (p. 179-180).

Despite the criticism of historical determinism that has been levelled against him, Spengler often confuses his reader with Faustian exclamations reminiscent of someone prepared for battle rather than reconciled to a sublime demise. 'No, I am not a pessimist,' writes Spengler in Pessimism, 'for Pessimism means seeing no more duties. I see so many unresolved duties that I fear that time and men will run out to solve them' (p. 75). These words hardly cohere with the cultural despair that earlier he so passionately elaborated. Moreover, he often advocates forces and th toughness of the warrior in order to starve off Europe's disaster.

One is led to the conclusion that Spengler extols historical pessimism or 'purposeful pessimism' (Zweckpressimismus), as long as it translates his conviction of the irreversible decadence of the European polity; however, once he perceives that cultural and political loopholes are available for moral and social regeneration, he quickly reverts to the eulogy of power politics. Similar characteristics are often to be found among many pets, novelists, and social thinkers whose legacy in spreading cultural pessimism played a significant part in shaping political behaviour among Europrean conservatives prior to World War II. One wonders why they all, like Spengler, bemoan the decadence of the West if this decadence has already been sealed, if the cosmic die has already been cast, and if all efforts of political and cultural rejuvenation appear hopeless? Moreover, in an effort to mend the unmendable, by advocating a Faustian mentality and will to power, these pessimists often seem to emulate the optimism of socialists rather than the ideas of these reconciled to impending social catastrophe.

For Spengler and other cultural pessimists, the sense of decadence is inherently combined with a revulsion against modernity and an abhorrence of rampant economic greed. As recent history a has shown, the political manifestation of such revulsion may lead to less savoury results: the glorification of the will-to-power and the nostalgia of death. At that moment, literary finesse and artistic beauty may take on a very ominous turn. The recent history of Europe bears witness to how daily cultural pessimism can become a handy tool of modern political titans. Nonetheless, the upcoming disasters have something uplifting for the generations of cultural pessimists who's hypersensitive nature--and disdain for the materialist society--often lapse into political nihilism. This nihilistic streak was boldly stated by Spengler's contemporary Friedrich Sieburg, who reminds us that 'the daily life of democracy with its sad problems is boring but the impending catastrophes are highly interesting.'

Once cannot help thinking that, for Spengler and his likes, in a wider historical context, war and power politics offer a regenerative hope agains thee pervasive feeling of cultural despair. Yet, regardless of the validity of Spengler's visions or nightmares, it does not take much imagination observe in the decadence of the West the last twilight-dream of a democracy already grown weary of itself.