South African Realities

by J MW

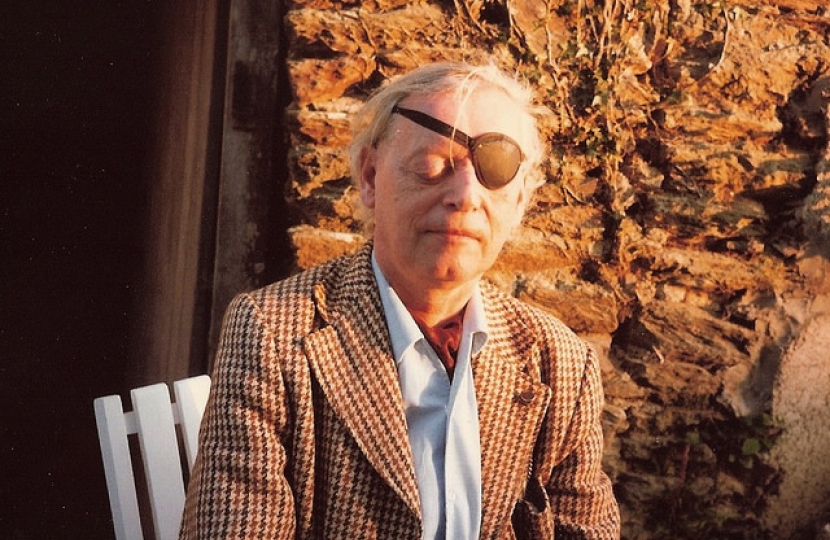

by T.E. Utley CBE (1921-1988)

Writing in The Times on 16 March on the eve of my first trip to South Africa, I listed the prejudices with which I set out: 'If I were a South African,' I wrote, 'I am pretty sure that I would now feel that in terms of morality the supreme need was to maintain public order, that this need would justify curtailment of the freedom of the press and of civil liberty generally, and that the moment was wholly unripe for the consideration of constitutional reform of a fundamental kind.'

How far have these prejudices survived their first brief contact with reality--a visit of three weeks, two of them spent as a guest of the South African Government, one as the guest of an old friend, an eminent retired South African diplomatist of strongly liberal inclinations and very little sympathy with President Both and the National Party?

In one respect my prejudices have been fortified. I did not realize the full extent of the power of the South African republic to sustain itself and to maintain by coercion what in Ireland is known as 'an acceptable level of public violence'. Last May, the Eminent Persons Group was predicting a steady acceleration of disorder which would end in a bloodbath.

I can find no one in South Africa, not the Right or Left, who now supports that thesis. The Government's emergency measures, whether you like them or not, have achieved their immediate object. A supporter of the United Democratic Front admitted as much to me: 'Nothing fundamental in the way of reform will happen for the next ten years,' he said. 'After that, it is possible that the system will collapse.'

This remarkable approximation to a restoration of public order has been achieved by a massive policy of administrative arrest and a display of overwhelming public force. In the process, I have no doubt there has been some physical brutality, though I have no doubt either that its extent has been exaggerated. Even liberal South Africans welcome the result, though they cannot approve the means.

In relation to the press, the government is paranoid, and this aspect of the state of emergency has become thoroughly ludicrous. Newspaper editors have to have lawyers sitting constantly at their side to avoid breaching some of the many regulations; but this does not protect the Government from perpetual attacks by the English-language press and damaging little notices declaring that newspapers have been produced under conditions of censorship.

The whole thing has the proportions of a considerable nuisance, rather than those of tyranny. What is more, the editor of one liberal newspaper told me that he thought the government's restrictions on the televising of violence were justified; television, he said, had become an incentive to disorder.

The essential point is that South Africa is not a banana republic constantly under the threat of political convulsion. It is maintained by a white army of indubitable loyalty to the State and by a massive civil service which at present is equally loyal. It is just possible to imagine a Right-wing coup but it is not possible, for the foreseeable future, to imagine a Left-wing coup. The speculations of progressives in the West about the imminent disintegration of the South African State are simply silly.

The strongest fortification of the State is, of course, the determination of the Afrikaners to survive. They believe that a unitary democracy based on one-man-one-vote would destroy them and destroy South Africa. They have no 'mother country' --they feel no sentimental allegiance to Holland, nor do the Dutch particularly like them. Unlike the English, they do not believe in the wisdom of concession. They are there to stay or to die.

This difference between the British and the Afrikaner approach to politics can scarcely be exaggerated. The essence of the English political tradition is the belief that the art of politics consists in discovering what is inevitable, and then brining the 'inevitable' about as smoothly as possible.

This particular technique is applied with special alacrity to white colonial populations, like the Southern Rhodesians, who can be sacrificed with little inconvenience to the electorate at home. To do them justice, however, the British also apply it to their own country--for example, in the 19th century, by enfranchising large numbers of illiterate people in the belief that it would all turn out right in the end and that anyway we could now set about educating our masters.

No such blithe irresponsibility prevails among the Afrikaners or indeed among the majority of first-language English whites in South Africa. They believe, with substantial justification, that one-man-one-vote tomorrow would mean a national ruin to which any other fate would be preferable. With these feelings I strongly sympathize and I do not believe that the coercive measures in which they are at present expressed are for the most part morally indefensible.

But in another respect, which I shall explore tomorrow, my prejudices have been altered.

This essay was first published in The Salisbury Review (Spring 1987)