Archive: Conservative Democratic Alliance - Article Selection

by Committee

Part of a new archiving project of past periodicals and standalone articles by the Traditional Britain Group and predecessors. These items are related to the Conservative Democratic Alliance, of which you can read more here.

- Rediscovering G.K. Chesterton – journalist, poet, polemicist and prophet (Link)

- What Are We To Think Of The Conservatives New Immigration Policy? (c 2004) (Link)

- Opera Wars (Link)

- The Rustle of Spring…(Link)

- The free-market and globalisation could wreck one corner of rural England (Lydd) (Link)

- This New Unhappy Realm (2007) (Link)

- Enlightened Enemies - The Hume - Rousseau Feud Re-Examined (Link)

- Utopian Idealists Against Our Nation And People (Link)

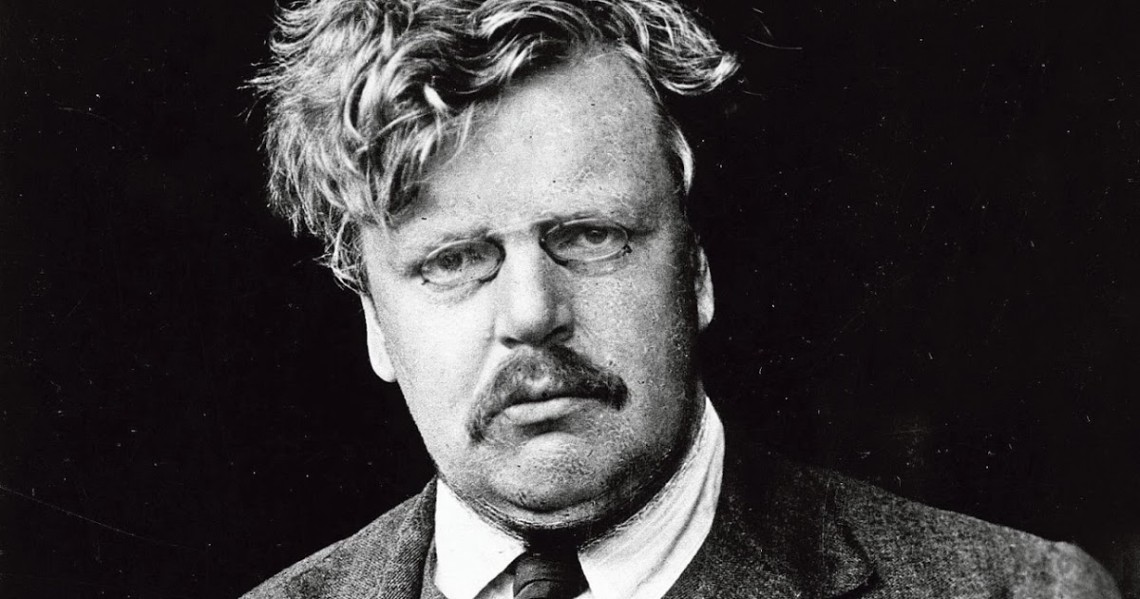

Rediscovering G.K. Chesterton – journalist, poet, polemicist and prophet

Famously named by George Bernard Shaw as "the Chesterbelloc" (or, at least, one half of that lumbering literary monster!), yet known by some of his young friends and admirers as "Uncle Chestnut", G.K. Chesterton was undoubtedly one of the greatest personalities of early 20th-century English literature and verse.

The lasting image of Chesterton (together with his old friend, Hilaire Belloc) is of a man who set forth in a billowing cloak to do battle with the scientific atheism of the Fabians; to state the case against Socialism, and for tradition, spirituality and the ancient Catholic Church; to write reams of verse, combative newspaper articles; and surreal, sometimes almost comical novels and stories which concealed fables and morality tales. Part-priest (but always laughing), a modern-day Dr. Johnson (and just as physically imposing), a Sir John Falstaff (but never a tragic figure), ‘G.K’ delighted – and continues to delight – readers throughout the world. Yet having said that, his presence today – ever so slightly – has faded.

Perhaps this eccentric gentleman in great tweeds, with his fantasies of self-governing London city-states (The Napoleon of Notting Hill), "flying inns", ruddy-faced publicans, sleuth-priests and suburban anarchists, is a little out-of-step with our bland, technological times. And yet, ‘G.K.’ is a man for our times – his messages, his prophecies, and his faith being entirely relevant to the immense problems of life, and the complexities of contemporary living.

This literary hero to so many traditionalists was born in the Kensington district of London, Campden Hill to be precise, on the 29th May 1874. Educated at St. Paul’s School, he was, as a young man, a vigorous participant in debates – even espousing what seemed like a prototype Communism! However, his unsettling rather leftish ideas as expressed at one schoolboys’ debate, and the notion that the state should govern economic life in the interests of all, was – perhaps – not as Marxist as one would think, as in later life he developed the idea of "distributism" – now, a rather esoteric, forgotten theory which aimed to transcend the materialism of both Socialist uniformity and rapacious, unrestrained global capitalism.

A distributist nation

According to Chesterton’s vision of Albion, the country would become a largely co-operative nation of smaller-scale enterprises; with skilled craftsmen making, trading or distributing goods; with property distributed as widely as possible, to encourage freedom and dignity – but with economic life not as an end in itself, but as a means to keep body and soul together. A country of suffiency, not greed – a country of skilled workers and worthy traders – a nation which had the church and tradition at its core: this is the bedrock of G.K’s England.

But the young Gilbert was by no means the certain, convinced, ready-made Catholic and philosopher. Joseph Pearce, in his detailed and lively 1996 biography of Chesterton, gives us a very different portrait of the great writer-in-waiting:

"He was asking the questions but, as yet, had not received the answers. Catholicism, Protestantism, paganism, agnosticism, socialism and spiritualism were all influences to varying degrees at varying times. During these formative years he caught these influences for short periods, much as a man catches influenza… He didn’t accept them as facts but fed on them as fads."

Literature and writing, however, were not his only enthusiasms. Chesterton (a keen doodler and cartoonist) was drawn toward the world of art, and enrolled at the renowned Slade School – although in time drifted away, partly disenchanted by the prevailing fashion of "the moderns", and partly having realised that his talents lay elsewhere. He also enlisted at University College London (1893), where his Latin teacher was the great A.E. Housman, although again, he departed prematurely from his studies. He later reflected:

"It was at the Slade School that I discovered that I should never be an artist; it was at the lectures of Professor A.E. Housman that I discovered

I should never be a scholar; and it was at the lectures of Professor W.P. Ker that I discovered I should never be a literary man."

A brush with the occult

By 1895, and with no degree, G.K. found himself confronted by the dilemma which affects so many aspiring writers – how to live from day-to-day, but still be able to build one’s experience and reputation. Chesterton supported himself by taking employment as a reader of manuscripts at Redway’s, a curious publishing house which specialised in occult texts. But the nature of some of the contributions which landed upon the reader’s desk surprised and shocked him, and he felt compelled to comment upon "the private asylums" from which the manuscripts must have emerged!

This bizarre backwater soon gave way to a more lucrative and mainstream world, that of the publisher T. Fisher Unwin – although Chesterton was still very much the "reader by day, and writer by night". This employment was to last until 1902, but a year after leaving academia, in the autumn of 1896, our literary hero was to find himself at a social gathering which changed his life. Accompanying his old friend from schooldays, Lucien Oldershaw, to the home of the Blogg family in London’s Bedford Park, Gilbert met "the elvish-faced" Miss Frances Blogg – and immediately fell in love.

For Chesterton, Frances corresponded to a romantic, even a religious ideal, and he gave expression to his love in a poem entitled, To My Lady. He wrote:

"God made you very carefully,

He set a star apart for it,

He stained it green and gold with fields

And aureoled it with sunshine;

He people it with kings, peoples, republics,

And so made you, very carefully.

All nature is God’s book, filled with his rough sketches

for you."

The poet proposed to his idealised love two years after their first meeting, in the green surroundings – not of the English countryside – but among the woods and trees of St. James’s Park, one of the great lungs of London. His deeply romantic and chivalrous disposition found its complete expression in Frances, and throughout their life together, Gilbert doted on his wife.

Their first home together was in another London setting, south of the Thames at Battersea.

A striking literary landscape

The solid, quiet inspiration provided by Frances was hugely important to G.K. and in the very early years of the 20th-century, he emerged as one of Fleet Street’s great columnists, principally for The Daily News – and later, for that once-great title, The Illustrated London News. Home was no longer amid the Victorian gloom of London’s Battersea, but in the leafy Home County of Buckinghamshire, where the writer and his wife would live for the rest of their days. But one of the most striking of Chesterton’s literary landscapes was in Berkshire – the chalk downland where the English army of King Alfred met the Danes in mortal combat, and from which Wessex and a true English nation emerged triumphantly.

The Ballad of The White Horse from 1911 is a stirring and romantic epic – full of the wonder of history and the past – the very magic and essence of England. One can almost imagine G.K. as a veteran of Alfred’s army – a great bulk of a man, a chieftain, elder or earl perhaps – drinking a tankard of ale before re-telling the story of heroic exploits on the high, green hills.

Stiff, strange, and quaintly coloured

As the broidery of Bayeux

The England of that dawn remains,

And this of Alfred and the Danes

Seems like the tales a whole tribe feigns

Too English to be true.

Yet Alfred is no fairy tale;

His days as our days ran,

He also looked forth for an hour

On peopled plains and skies that lower,

From those few windows in the tower

That is the head of a man.

In these lines from the Ballad, the reader is shown both the romance, the "fairytale" side to our history – and the sense that despite the drama and mythology, Alfred and his men saw the very contours of the hills which we can see today. For Chesterton, the past and the present are indissolubly linked through landscape and legend.

England under Islam

Two years later, the author entered a world of pure make-believe in his novel, The Flying Inn. The book begins in the perfect English seaside landscape of Pebbleswick – a completely fictional place – but perhaps a compound of Eastbourne, Deal, Selsey, or a dozen other towns or villages by the sea. But it is the political and religious landscape of The Flying Inn which is so remarkable – a strange England in which the ruling class has fallen under the spell of Islam – the traditional pub and the practice of beer-drinking having been outlawed by the imperious Lord Ivywood, ruler of this new unhappy land. An outraged and defiant publican, Humphrey Pump, and his friend, the Irish mariner, Patrick Dalroy, decide that they will not be crushed by the unnatural and alien diktat of the regime, and so take to the open road as fugitives – their barrel of ale and pub sign the last symbols of defiance of the downtrodden English.

Despite the serious purpose of the tale, there are moments of great mirth, and Chesterton unleashes one of his most famous "drinking songs" upon us – The Rolling English Road. Just as The Ballad of the White Horse, unites past and present, so this beery verse creates a similar sense of English unity over the centuries.

Before the Roman came to Rye or out to Severn strode,

The rolling English drunkard made the rolling English road.

A reeling road, a rolling road, that rambles round the shire,

And after him the parson ran, the sexton and the squire;

A merry road, a mazy road, and such as we did tread

The night we went to Birmingham by way of Beachy Head.

By the time the revellers have come to the end of their rolling journey, they have passed to

"paradise, by way of Kensal Green" – a line that seems to symbolise an important ideal of Chesterton – that heaven itself is an overlooked suburb or an English town that is thought to be commonplace.

Sadly, but perhaps not too surprisingly, The Flying Inn (at least to my knowledge) exists in no modern edition. Modern sensitivities being what they are, the swashbuckling story of plucky natives fighting a foreign regime – with a climactic battle between alien overlords and the people – might be considered too controversial. However, if you ferret through any old bookshop, there is a chance that – beneath the dust – you will chance upon an old copy of this prophetic work.

The unhappy lords

Finally, let us leave Chesterton not in any one place, but in another mood of grave prophecy – a landscape of the mind, if you will. Of all his poems, The Secret People seems to speak out to true, traditionalist Englishmen and women the world over – especially in these anxious and disturbing times when so many of our institutions have been changed, or have disappeared altogether – where nothing seems right. Never harsh, never strident – the emotions which Chesterton evokes might yet inspire the people of the land he loved…

They have given us into the hand of new unhappy lords,

Lords without anger or honour, who dare not carry their swords.

They fight by shuffling papers; they have bright dead alien eyes;

They look at our labour and laughter as a tired man looks at flies.

And the load of their loveless pity is worse than the ancient wrongs,

Their doors are shut in the evening; and they know no songs.

We hear men speaking for us of new laws strong and sweet,

Yet is there no man speaketh as we speak in the street.

It may be we shall rise the last as Frenchmen rose the first,

Our wrath come after Russia’s wrath and our wrath be the worst.

It may be we are meant to mark with our riot and our rest

God's scorn for all men governing.

It may be beer is best.But we are the people of England; and we have not spoken yet.

Smile at us, pay us, pass us. But do not quite forget.

Chesterton died at his Buckinghamshire home in the June of 1936. With the exception of his close friend, Belloc, there was no-one remotely like him – and his place has yet to be filled. Journalist, novelist, poet, polemicist, visionary, thinker, crusader – ‘G.K.’ surprised, startled, educated and won over readers and audiences throughout the world to his unique wisdom and philosophy. There were giants in the land in those days…

What Are We To Think Of The Conservatives New Immigration Policy? (c 2004)

Michael Howard has attracted considerable criticism from the usual suspects for the party's newly-unveiled policies on immigration which,Trevor Phillips of the Commission for Racial Equality hyperventilated, "will allow

racists to put the worst possible construction" on them.

With denunciations like these, it would be easy to warm to the policies and to Michael Howard (and while it is heartening to note how the public mood has changed so drastically on this issue, with the Left reeling and

defensive) immigration-sceptics should not offer their unqualified support unless more details are forthcoming.

It is difficult to see how we can yet gauge the "toughness" or otherwise of Mr Howard's policies, in the absence of any specific figures as to his proposed upper limit on legal immigration. One might have hoped, however,

that bearing in mind the considerable racial tension that currently exists across the UK, the pressures on Britain's infrastructure and environment and the speciousness of the various economic 'arguments' for mass

immigration - not to mention the ongoing security concerns - a truly courageous policy might have featured a moratorium on legal immigration for at least five years. And resiling from the 1951 UN Convention Relating to

the Status of Refugees, whilst a long overdue reform, has already been called for by various senior Labour figures, including Jack Straw and Tony Blair.

These two latter individuals have suddenly gone very quiet on thissubject; how do we know that the Conservatives will not do likewise? In the event that the Conservatives win the election, how can those who vote for them on the strength of this policy be sure that the policy will be adhered to? Successive Conservative leaders have promised one thing on immigration (and Europe), but failed to deliver, with the emasculating effects that are all too obvious in our daily lives. David Davis is supposedly the 'hard man' of the party, yet he had a ludicrous panic attack over the recent book by immigration whistleblower Steve Moxon, offering to chair the launch one day and then pulling out at the last minute, frightened by an article in the Independent. Such behaviour implies that the Conservatives may be lacking in the essential moral fortitude to slay the race relations industry hydra.

If Labour has indeed signed away control over our immigration policy to Brussels, as is now being suggested, this was surely an inevitable development - given the nature of the EU organism, which seeks constantly to accrue more and more power at the expense of national parliaments, and its inbuilt political bias, which will always be statist and politically correct. Bluster about 'repatriation' of powers from Brussels is empty rhetoric, as the EU is inherently imperialistic and totalitarian, and will never tolerate independent actions of this kind. The only solution to the

EU's centralising drift is for the UK to quit the EU once and for all.

Mr Howard has also said that asylum will be reformed, and that a ceiling will also be put on the number of refugees. These are vital reforms – yet he has not indicated whether or not said refugees will be permitted to stay in the UK, once the situation in their home countries has eased. He has pledged extra security at ports and airports, which is very welcome - yet it is fair to point out, as Labour has done, that the party is simultaneously calling for massive cuts in the Immigration Service budget. Cuts in this policy area would be a false economy, as there are enormous

hidden fiscal and social costs of mass immigration.

The Conservatives need to think about this subject long and deeply. They need to reject woolly thinking like that espoused by the Daily Telegraph's Andrew Gimson, who in a recent column opined that immigrants were "natural Conservatives" who "admire hard work, self-reliance, religion, the monarchy and the British tradition of liberty". To put it kindly, this is delusional. While this may have been partly true of West Indian and African immigrants during the 1960s (although the overwhelming majority of postwar immigrants and descendants of postwar immigrants vote for Labour, according to Operation Black Vote), one fears that Mr Gimson's beguiling stereotype of forelock-tugging black and brown yeomen is now several decades out of date. There is little evidence, to say the least, of any such qualities among more recent immigrants.

If Mr Howard and his strategists can work out a courageous and comprehensive formula on race that takes into account all the varying aspects and covers all the bases - if they can express this in simple, robust language - and then stick to their guns when faced with the inevitable orc-shrieking - even at this late hour they may yet just manage to squeeze back into power.

FROM LEDBURY TO LEYTONSTONE, LABOUR'S IN TROUBLE!

Over decades, Britain's 'responsible' politicians have between them managed to turn one of the world's most stable, most civilized and freest states into a disunited, neurotic and increasingly unfree one - where the Western legacy hangs on a knife-edge, overwhelmed by mass immigration and totalitarian 'political correctness'.

Whatever the changes of government, what were once far Left causes have long since become mainstream causes, and far-Left values have triumphed, o the extent that even the Conservative Party dare not dissent from the new orthodoxies of indefinable, selectively-applied 'human rights' allied to multiculturalism'.

The resultant increased lawlessness and unhappiness have made their presence felt more and more, even within the precincts of the Palace of Westminster, such as when, on the 15th of September, pro-hunting demonstrators got all the way into the House of Commons. This unwonted intrusion of reality badly frightened anti-hunting MPs, who are accustomed to deference from the people they so clearly regard as moral inferiors.

While the demonstrators achieved little except, probably, to hasten the end of the traditional Commons security arrangements - how the media sneered at the 'men in tights with swords' - it was salutary to ruffle MPs' feathers, who denounced in trembling voices those who had irrupted into their politically correct pipe-dream. The Labour MP David Winnick said that the incursion was "the most disgraceful act of hooliganism" - somewhat ironical from a politician whose entire career could be characterised as an "act of hooliganism" against Britain.

There were similar outpourings from Peter Hain, Leader of the House of Commons - a curiously legalistic position for a man who made his name organising disruptions of cricket matches. It does not seem to have occurred to those who emoted about 'the dignity of parliament' that dignity needs to be earned. Laws like the proposed ban on hunting are unworthy of a great legislature, and are in any case likely to prove impossible to enforce.

One feels sorry for the police who risk their safety to protect worthless laws and the worthless politicians who have dreamed them up. Ideally, the police and the hunters would be on the same side of the barricades, united in the great cause of giving Britain back to the British. Whatever the outcome of the hunting legislation, perhaps some of the strength of feeling, imagination and organisational skills that have been displayed by the countryside lobby will not be entirely dissipated and these positive energies can also be deployed in campaigning to leave the EU, attempting to stop immigration and clamping down on genuine criminals.

Tony Blair is supposed to be a practical politician, so why is he unnecessarily alienating a group of potential voters? Why did he, as Lord Deedes put it pithily in the Daily Telegraph, "make an ass of himself" over hunting? Hunters seem to be being victimised for no reason other than to gratify the emotional spasms of backbench Labour MPs - for whom the perceived welfare of foxes appear to be of more moment than the rural economy, the war in Iraq, the EU, the NHS or even the welfare of the working classes.

The answer is that the Prime Minister, who is a highly-strung, almost hysterical, man, is afraid. He knows that he and his government are increasingly unpopular from Ledbury to Leytonstone - to the extent that ministers are now actually physically afraid to venture out into the countryside. This currying of favour with his parliamentary cannon-fodder is a kind of ideological circling of wagons against the menacing world outside. For the moment, the armed police can keep the Native Britons at bay - but Blair is fast running out of friends and ammunition.

Yet while we may cheer inwardly at Labour's proximate predicament, we should consider two things. First, who will take over from them? The Conservatives are demoralised and divided, and haemhorraging support to the UKIP, and so may lose the next election by default. The UKIP is still regarded as a single-issue party, while the BNP is presently regarded as 'beyond the pale' - and both are, in any case, hampered by the first-past-the-post electoral system.

A more long term consideration is that this hunting, and similar, legislation will merely widen the gap between rulers and ruled - a gap that future, more responsible governments may find it impossible to close. The essential legacy of New Labour to its eventual successors is likely to be mammoth legislative mistakes, and massively increased social mistrust. Any putative government worth its salt will have to be able to demonstrate convincingly not just that it can repeal hasty laws, but also that it can rebuild trust and patriotism in the country at large.

Opera Wars

A few years ago, some inclusively-minded ‘cultural’ oracle proclaimed ‘All operas are left-wing’. Well, I suppose many works written from the Enlightenment onwards might be described as conveying a ‘liberal’ message, Beethoven’s Fidelio and Verdi’s Don Carlos being obvious examples. In Brussels, Auber’s La Muette de Portici, inspired by the Neapolitan revolt against the Spaniards, touched off a real-life revolution against the House of Orange.

But the truth is that none of this can be said of early opera, once a closed book, but now an important part of the modern repertoire. From the philosophical and historical researches of the Florentine Camerata, to the dawn of the Enlightenment and beyond, opera manifested itself as an art form which, with its casts of heroes, gods and wise princes, tended to glorify absolute monarchy. Absolute monarchs, after all, more often than not paid the piper. True, opera prospered in republican Hamburg and for a meteoric but glittering period in constitutional England under Handel, Bononcini and other composers of the first rate. In London, however, the art remained very much an exotic import, and it is perhaps significant that the Dutch Republic, for all its wealth and love of novelty, remained an operatic desert.

Yet a revolution lay on the horizon. Naples was very far from being a rechtsstaat, let alone a democracy, but in the streets of the most musical of European capitals the common people sang from morning to night, finding a freedom in music they were denied in the field of politics. It was in Naples in 1733 that a brilliant young composer, Giovanni Battista Pergolesi, produced a simple one-act comic opera La Serva Padrona, which employed folk-song like arias to tell a charming burlesque story of a cunning maid who tricks her elderly master into marrying her.

The piece was originally no more than an intermezzo inserted between the acts of Pergolesi’s opera seria Il Prigioniero Superbo, a work that rapidly disappeared from view. La Serva Patrona, however, was an immediate hit. Three years later Pergolesi lay dead at the age of 26, but his musical offspring survived to conquer Europe.

In 1752, La Serva Padrona was given in Paris by an itinerant Italian troupe of comic actors, who needed little singing talent to perform the simple work. Immediately the cause of this new form of opera was taken up by men of letters who, needless to say, had ulterior motives for their partisanship. The resultant controversy, conduced in the columns of newspapers and in pamphlets was celebrated as the "Querelle des Bouffons" (War of the Comedians) and may to some extent be seen as a proxy for the largely suppressed political arguments of the day.

The debate highlighted the differences between what was characterised as the vibrant and progressive character of Italian opera and the stultified traditions of French Tragédie-lyrique. Now this is an interpretation which may be strongly challenged, but what is without doubt is that in France, under the patronage of the absolute monarchy, an art-form had developed which had become exclusively French, for all its Italian roots.

In the operas of Monteverdi and Cavalli we find continuous streams of harmony with an absence of discrete songs or arias. This was the tradition that Jean-Baptiste Lully, himself an Italian by birth, had brought to the court of Louis XIV and which, after his death had continued as if preserved in aspic. Operas by Lully remained in the repertoire for decade after decade, and were joined by the imitative works of lesser talents such as Delalande and Destouches.

Certainly, with his début opera Hippolyte et Aricie in 1733 Jean-Phillipe Rameau had brought about a much-needed revolution in Tragédie-lyrique, but it remained still Tragédie-lyrique; sung in French, relying upon semi-declamatory vocal harmonies rather than melody, and eschewing the services of the talented and glamorous castrati who had taken the rest of Europe by storm.

As it happened, the 1752 performance of La Serva Padrona coincided with a revival of Destouche’s Omphale, a work which was now 51 years old. This was the catalyst for the philosophe Grimm, who launched a stinging attack upon the creaking work and upon the Opera itself. "The composer is dead" wrote Grimm, "and his work had little enough life in the first place".

Grimm’s Lettre sur Omphale whipped up an immediate storm, with men and women of fashion and learning taking up the cudgels either for the cause of cultured French opera or for the demotic, easy-going manners of the Italian interloper. Now came to the fray Grimm’s friend, the expatriate Swiss Jean-Jacques Rousseau, on this occasion motivated less by political ideology than by motives of revenge.

When Rousseau came to Paris in 1743, he had done so as a would-be composer and musical theorist, and his idol was the greatest living French composer, Rameau. The austere and cerebral Rameau, as famous for his works of musical theory and philosophy, as for his keyboard publications, had won new laurels when he started to compose opera at the relatively advanced age of 50. This giant, who had absurdly proclaimed music to be first among the sciences, was widely hailed in France as ‘The Newton of Music’.

The newcomer had brought with him a plan for a revolutionary new system of musical notation, which rapidly sank without trace. Rousseau brought also the sketches for an opéra-ballet entitled Les Muses galantes in blatant imitation of Rameau’s highly successful work Les Indes Galantes. The intended tribute was brusquely rebuffed by the notoriously rude Rameau, and Rousseau now conceived in his heart an implacable hatred for his former hero.

By 1752, however, Rousseau had himself found fame with Le Devin du Village, a miniature French comic opera of peasant life which was performed before Louis XV and the court at Fontainebleau to enormous acclaim. The king’s unmelodious voice was heard around the palace singing Rousseau’s hit aria J'ai perdu mon serviteur and Rousseau, had his daemon not led him in a different direction, could have claimed a freely-offered place as a favoured and cosseted court composer.

Now, with his place in the operatic pantheon apparently assured, Rousseau turned with relish to uphold the cause of Italian Opera buffa against the aristocratic grandeur of the Paris Opera and, therefore against the living symbol of that grandeur, Jean-Philippe Rameau.

Rameau, who himself had years before been denounced as an anti-traditionalist, remained aloof throughout the controversy, but it must have pained him deeply to see his wealthy patron, the fermier-général Le Riche de La Pouplinière, drawn to the side of the ‘Italians’.

Meanwhile Rousseau’s assault upon French opera in particular and French music in general became ever shriller. Finally in Lettre sur la musique Françoise, published the following year, he overstepped the mark completely.

"I think that I have shown that there is neither measure nor melody in French music, because the language is not capable of them; that French singing is a continual squalling, insupportable to an unprejudiced ear; that its harmony is crude and devoid of expression and suggests only the padding of a pupil; that French ‘airs’ are not airs; that French recitative is not recitative. From this I conclude that the French have no music and cannot have any; or that if they ever have, it will be so much the worse for them."

Paris reacted with outrage. Rousseau’s free pass at the Opéra was summarily withdrawn, he was allegedly abused and kicked when he attempted to enter the building and the members of the orchestra burned him in effigy. With characteristic paranoia, Jean-Jacques decided that there must be a plot to murder him and in 1754, he decamped to his Genevan birthplace. This was to be the first leg of that tormented yet productive journey through an unsympathetic Switzerland which led him, catastrophically, to England before his final return to France,

Now Rameau, who had carefully avoided being drawn into the opera controversy, could not resist taking a swipe at his stricken tormentor, and he launched an attack on Rousseau's contributions to the musical entries in the Encyclopédie. To Rameau’s chagrin he now became the personal object of counter-attacks from d'Alembert and Diderot. The lasting legacy of this quarrel was Diderot’s brilliant satirical dialogue Le Neveu de Rameau.

Wounded by the criticism from his fellow-intellectuals, Rameau retreated into a crabbed and disillusioned old age and died in 1764 at the then considerable age of eighty-one. The daring and dazzling effects of his last, unperformed, stage work Les Boréades proved that for all his disenchantment he remained the unchallenged king of French opera.

In 1767 Rousseau fled to France from England in panic, his head whirling with fantasies of planned kidnap and assassination. He relocated to Paris in 1770 and lived in quiet seclusion, a shadow of his former self.

Now to Paris came Christoph Willibald Gluck, the ennobled scion of Bohemian foresters. In Vienna Gluck had been music tutor to the Hapsburg princess Marie Antoinette, who in 1770 his pupil married the Dauphin, the future Louis XVI . In 1774, the same year that Marie Antoinette became Queen of France, Gluck obtained a contract to write for the Paris Opéra.

Years before, Gluck had declared himself a disciple of Rousseau. Orfeo ed Euridice, received its premiere at Vienna in 1762, and with its tiny cast and pure melodies stripped of superfluous ornament, Gluck seemed to have realised the apotheosis of the type of opera exemplified by La Serva Padrona and Le Devin du Village.

Yet Orfeo had been this and much more. Gluck’s little masterpiece consciously integrated drama, music and dance in a manner more reminiscent of the stage works of Rameau. His first work for Paris Iphigénie en Aulide (1774) took the process a stage further, in effect synthesising the French tradition of Tragédie-lyrique with that of Italian opera.

Yet the premiere of Gluck’s superb work gave rise to a storm of controversy. Unlike the Querelle des Bouffons, which had deep intellectual roots, the inspiration of this row seemed to owe more to a general chauvinistic resentment of a clever foreigner who had set out to teach the French their business. So, with a breathtaking absence of logic the patriotic party chose as their champion an Italian Niccolò Piccinni, whose light-hearted if somewhat lightweight opere buffe had amused the Parisian public for years. In her memoirs the celebrated portraitist Élisabeth-Louise Vigée-Le Brun gives a vivid picture of the new battleground.

The love of music was so general that it occasioned a serious quarrel between those who were called Gluckists and Piccinists. All amateurs were divided into two opposing factions. The usual field of battle was the garden of the Palais Royal. There the partisans of Gluck and the partisans of Piccini went at each other with such violence that there was more than one duel to record.’

1774 saw the premiere of a recast and extended version of Orfeo, translated into French with the former castrato title role now given to a tenor, in accordance with Parisian taste. The production was generally well received, and in that year a poignant meeting took place between the ailing and reclusive Jean-Jacques and his admirer, the glamorous Chevalier. The two men got on remarkably well. Rousseau died four years later, one of his last published writings being an enthusiastic review of Gluck's opera Alceste, a reinterpretation of the very same story which had inspired one of Lully’s greatest masterpieces.

So, in a sense, the story had come full circle, with little more than a decade to run before the world-shattering events of 1789. In 1779 Gluck suffered a stroke and returned to Vienna, leaving the Paris Opera in the capable hands of his protégé Antonio Salieri,

In 1787, the year of Gluck’s death, Salieri scored a huge triumph with Tarare, to the libretto of Beaumarchais. In the tradition of Gluck’s reforms Salieri’s music served the drama, and what a drama! The death of a royal tyrant and his replacement by a patriotic and popular commander uncannily reflected the unstoppable march of French history. As the people crown Tarare, the final chorus proclaims ‘Your greatness comes not from your rank, but from your character.’

The politics of opera had been replaced by the opera of politics.

Mike Smith

The Rustle of Spring…

After the deprivations and gloom of January and February, the time has now come for the rediscovery of mild breezes (rather than freezing winds!) and the warm rays of the sun. Music can help us along the way, especially with such famous works as the piano piece, The Rustle of Spring – once a popular item in salons and on the wireless. This lyrical impression for the piano was written by the Norwegian composer, Christian Sinding (1856-1941), and to my ears is just as evocative as Vivaldi’s more well-known “Spring” from his evergreen and ever-popular The Four Seasons.

On the downland

As I have just mentioned, Sinding died in 1941 – the same year in which Frank Bridge, an English composer (and teacher of the young Benjamin Britten) left this life. Spring was a particular inspiration to Bridge (as it was to his young protégé), and in the 1920s the senior composer embarked upon a breezy, involved orchestral work whose working title was “On Friston Down”. Bridge later changed the name of his ambitious piece to Enter Spring – and in its 25-minute span, the composer manages to evoke all the sights, sounds and feeling of a day in early March or April, including an exquisite woodwind passage suggestive of birdsong.

Other native composers to have responded to springtime include Ernest Farrar – a man born in the then small town of Lewisham in 1885, but who met a tragic end when serving on the Western Front in 1918. Farrar’s music has only recently been rediscovered and his creation of a May morning in English Pastoral Impressions conjures a radiant daybreak, long before the horrors of mechanised warfare intruded and shattered the idyllic England of those far-off days. Although a non-combatant, Frank Bridge felt the pain of the war very acutely, and dedicated his strange, brooding orchestral work There is a willow grows aslant a brook to Ernest Farrar.

An impression of time and place

Another lesser-known English composer was John Foulds – a truly avant-garde figure in his day – who, after the First World War, composed a huge World Requiem designed in its vastness to transmit a sense of peace and reconciliation to the whole of humanity. Foulds later made his home in India, inspired by Eastern philosophy and attitudes, but he did pay tribute in music to his native country. One of Foulds’s “Impressions of Time and Place” is entitled simply – April, England – a fervent, noble and deeply beautiful work for large orchestra, which seems to contain its own “rustle of spring”.

Spring Symphony

Earlier on, I made reference to Benjamin Britten. This famous musician, founder of the post-war Aldeburgh Festival, and our country’s greatest operatic composer since Henry Purcell in the 17th century, took to the theme of winter’s disappearance with great relish. Britten loved his native Suffolk, and it is said that whilst driving through the county on a particularly fine morning at the beginning of the year – with blossom and country houses coming into their own – the works of the great Elizabethan poets came to mind.

His Spring Symphony of 1949 was the result – a paean to Nature and the sun for three soloists, a boys’ choir, a large symphony chorus, and symphony orchestra – complete with a cow’s horn, which is blown at the work’s conclusion in a spectacular Mayday procession. Originally commissioned by the Boston Symphony Orchestra, this cornucopia of operatic-like choruses, yet combined with the more intimate spirit of an English song-cycle, received its first performance before a Dutch audience, under the baton of Eduard van Beinum. One of the poets set by the composer was Richard Barnfield (1574-1627). The tenor soloist (with harp accompaniment) sings:

And when it pleaseth thee to walke abroad

Abroad into the fields to take fresh ayre,

The meades with Flora’s treasure should be strowde,

The mantled meaddowes, and the fields so fayre.

Britten had a remarkable capacity to marry words to music, and his choice here is truly “open-air” and outdoor in its swiftness and sense of freedom.

Violent reaction

Finally, we can turn to Russia for a mighty bear-hug to embrace the new season. Rachmaninov’s cantata Spring seems to rush forward with the strength of a spring torrent; Glazunov’s version of the progress toward summer is balletic and carefree, gentle and carefully painted with delicate orchestral colour; but Stravinsky’s shattering The Rite of Spring brings to life a pagan world – an eruption of nature and of primitive human celebration. Stravinsky claimed that the inspiration for his Rite came from a two-hour period in the Russian countryside in which he actually experienced the very moment of spring’s arrival.

At the work’s first performance in Paris in the May of 1913, a riot ensued – so jagged and relentless was this astonishing composition that it prompted a violent reaction from some sections of the audience. Stravinsky had, at a stroke, moved music into a new era and sound-world, whose motion and gravity would pull art toward an abstract and atonal future – the legacy of men in our own era such as Pierre Boulez and his disciples. But could Stravinsky have sensed the violence that was to engulf Europe a year later; the violence that was to destroy (among many millions of others) the life of his fellow-composer, Ernest Farrar in a blasted war-scape of trenches and hollows from which all Nature had been driven?

Restlessness and rediscovery

Stravinsky, of course, would scarcely (if at all) have known of Farrar or his music, and for most of the 20th-century it seemed that Stravinsky’s “violence” had triumphed over the more remote pastoral visions from the provinces of England. Could it be, though, that the restlessness and anxiety of the old century has given way to a desire for simplicity and nearness to the soil, which is somehow represented by the rediscovery of Farrar and Foulds?

Bridge, Farrar, Stravinsky, Sinding, Britten, Vivaldi – centuries of music and completely different musical voices, but with one thing in common: an emotional response of the deepest kind to Nature, to home-landscapes and the universal regenerative powers of the season.

However, the peace of Romney Marsh could be shattered forever if the go-ahead is given to the Middle Eastern company which owns the airport, to run large-scale passenger services. Already, there are some ominous signs – and signposts. For example, on driving up to the gates of Lydd airport, the passenger is told that he or she is at “London Ashford Airport” – a very imaginative approach indeed to marketing and geography, given that Lydd is a 70-mile or so drive from the capital city (which already provides the burgeoning population of the South-East with three airports).

Global business lobby

A number of environmental action-groups have been formed to counter the threat of this latest proposal for airport expansion (the North Kent marshes, with their unique wetland bird habitats were spared a couple of years ago after furious local protests); and the issue has been brought to public attention in the form of some evocative newspaper articles about the spirit of Romney Marsh. But as ever, the global business lobby exercises huge power – and perhaps surprisingly, there are also many individuals within Kent business organisations and local authorities who believe that the only raison d’etre to life is to build new motorways, ring-roads, and more ring-roads to run rings around the existing clogged up traffic system. “If we need a new road, build it” exclaimed one business-Stalinist at a county local business convention in Ashford in 2001 – the “gentleman” apparently having not a single thought for any other consideration or consequence.

Let us be clear what is at stake here. As the Campaign to Protect Rural England warned, not only would the expanded airport cause immense problems with overloaded marshland roads, but the daily impact of Boeing 737s roaring across the small coastal communities and villages – trailing kerosene in their wake – would make for an environmental disaster. But the problem would not be confined simply to the marshland… Circling jets, waiting for their landing slots, would disturb the peace, quiet and solitude of the North Downs Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty – the mass of aircraft making it increasingly difficult to sustain the rich and enriching local bird population, particularly rare species, and the patterns of bird migration across nearby Dungeness, home of an RSPB reserve. Once again, CPRE provides a perfect clarification of the matter at hand… and what a pity that one leading Conservative and Cameronite chose to deride this valuable body of concerned and dedicated volunteers as “the campaign to preserve posh people’s gardens” – a truly depressing comment for a supposedly “green party”.

Artificially-inflated population

In an increasingly overcrowded South East, with an artificially inflated population, and the ongoing phenomenon of the London overspill moving further and further away from the horrific problems of congested and crime-ridden Inner London, there has never been a greater need to preserve what remains of the remoteness of the Kent countryside. And in the case of Romney Marsh, there is so much within that “fifth continent” which stands for the England which we need so desperately to preserve: the reed-beds and heron-priested banks of dykes and waterways which criss-cross the landscape; the mediaeval church of St. Clement at Old Romney – which looks as though it has grown roots into the very soil; the vast skies and sunsets over the Channel coast, where the Home Guard kept watch in the dark days of the last war. I wonder if such places would ever inspire David Cameron to venture down for an environmentally-concerned photo-opportunity – or is “the environment” just about expensive trips to the North Pole, US Government spokesmen talking about “carbon footprints”, or the plight of the Third World or faraway countries and indigenous peoples?

Once again, the future of a recognisable and rooted place, with its own special culture and local quirks – not to mention a rare ecology, natural history, and treasured tranquillity – stands or falls on the decision of faceless officials, and the whims of foreign entrepreneurs. And despite the current clamour for “green taxes” and for the increased taxation of air travellers, there seems to be a strange predisposition on the part of our rulers toward building new airports and extra runways – a peculiar mismatch of aims! For hundreds of years, Romney Marsh has maintained its sense of separation and feeling of wild mystery – providing a sanctuary for many weekend visitors, and a pleasingly rural habitat for the people who live there. How terrible that the slow passage of time – the essence of any civilised or conservative society – should be sacrificed to the short-termism of the global free-market, and the balance-sheets of the money-men and philistine modern state bureaucracy. We need to preserve the natural and national heritage of our island – we need to save Romney Marsh.

This New Unhappy Realm, Derek Turner

Millions of years ago, in 1999, a fresh-faced Tony Blair said that he wanted to achieve “a better quality of life”. His proposed solution consisted of: “That is why sustainable development is such an important part of this government’s programme…and devising new ways of assessing how we are doing.” While environmental concerns are important, and while methodology does matter, as social analysis this left something to be desired.

In 2002, there was a government “life satisfaction” seminar, which led to an unofficial “analytical paper” filled with that inimitable, abominable New Labour mixture of management-speak and aggrievedness, which advocated “a happiness index”, “teaching people about happiness”, “more support through volunteering”, “a more measured work-life balance” and – surprise, surprise – further taxation of the wealthy.

No-one can doubt that happiness is important. Too many of Britain’s streets are gloomy, ugly and suspicious avenues, populated by a shuffling, scruffy mass who look almost as if they are living through some terrible catastrophe. We live in a society woefully lacking in public expressions of confidence and joie de vivre. Every aspect of life seems filled with quiet hopelessness, and a secret sadness.

‘Happiness’ pundits say that we are unhappy partly because we are made to feel inadequate by glossy advertising, because money is unevenly distributed, because we have long journeys to work, because we eat badly and don’t take enough exercise. There is something in what they say. It certainly would not do any harm if we were exposed to fewer advertisements of the sort that make children demand (and usually get) the latest trainers, if more people were a little richer, if we didn’t need to spend so much time travelling (and could thereby spend more time with family and friends) and if we ate fewer junk foods. And perhaps, as has also been suggested, some people would benefit if the NHS were to expend more time and resources on improving people’s satisfaction levels.

The happiness theorists take a tentative step into political incorrectness, by realizing that marriage is beneficial for individuals (and so society), adding to levels of satisfaction and even life expectancy. As the 2002 “analytical paper” was co-written by one of Tony Blair’s chief advisers, perhaps some of this kind of thinking might even find its way into government policy some day.

David Cameron is surfing the well-being wave too, telling the Google Zeitgeist Conference in 2006 that “Well-being can't be measured by money or traded in markets. It's about the beauty of our surroundings, the quality of our culture, and above all the strength of our relationships… politicians should be saying to themselves ‘how are we going to try and make sure that we don't just make people better off but we make people happier, we make communities more stable, we make society more cohesive’.” (quoted on bbc.co.uk, 22 May 2006).

We should applaud examination of the causes of unhappiness. But all these pundits aren’t cutting deeply enough. For people who say (correctly) that economics is not enough, many of their suggested improvements are themselves highly reductive.

The chief reason for unhappiness is, of course, the loss of religious faith. When God is removed from the cosmos, then many things automatically become existentially pointless, and the cruel, freakish, random nature of the universe is made brutally apparent. As the causes of this lie outside politics (and even beyond the established church) we must absolve the politicians of blame for this phenomenon.

And as an agnostic (albeit a pro-Christian one), I am myself a part of the problem, and it would be hypocritical of me to advocate what I do not believe myself. But there are things that politicians could do today to make Britain happier, if only they had the courage and the vision.

For instance, one of the deeper reasons that Britain is unhappy is because so many parts of it are plain ugly. While modern architecture is improving, there are still huge swathes of Britain that are dominated by 1960s tower blocks, 1970s shopping precincts filled with the same shops, bungalows and caravan parks and houses with PVC windows, industrial estates, ring roads and motorways. “To love your country,” said Edmund Burke, “your country must be beautiful”. But who could love Stevenage, or Cumbernauld, or Corby, or Croydon? David Cameron is right to select this as a major cause of unhappiness. More sensitive (and streamlined) planning controls would, in time, make a massive difference to Britain’s landscapes, and accordingly Britons’ happiness.

But society is ugly too. What else could we expect in a country whose ruling class includes John Prescott, Piers Morgan and Jordan? Who could love the Britain of the Sun and the Mirror, of football hooligans, of lachrymose social workers and whining teachers, of late-night vomitings and back-alley stabbings, and fag-smoking 13 year old mothers-to-be? David Cameron famously, fatuously said that “I love the Britain we have today” – but he is a member of a small and shrinking minority. It is less clear what could be done to alleviate this sickness of the soul, but statesmanlike politicians could, at least in theory, start to arrest the rot, one social sector at a time, through judicious financial and welfare reforms.

Another reason for unhappiness is that Britain simply has too many people – with more arriving all the time. It is difficult to avoid feeling that Britain is suffering from “crowding stress” – the phenomenon that occurs in overcrowded rabbit burrows, where there is constant fighting over space, mates and food, and the does re-absorb their litters rather than bear them into a world where room and nutrition cannot be guaranteed. In modern Britain, there are simply too many houses, too many roads, too many cars, too long queues for doctors and dentists, too much pollution and too much noise.

Another reason may be the relatively small proportion of Britain’s population that is under 25. Young people are naturally ebullient, whereas older people are more likely to be querulous and obsessed by comfort. More old people equals more grumpiness.

A deeper possible reason is simultaneously the most widely discussed and the least addressed – the vast chasm between rulers and ruled. This really is the fault of politicians, who claim to respect the vox populi, but who really push their own agendas – on everything from capital punishment to immigration. They say grandly when challenged that they are representatives rather than delegates; when one surveys the mess of modern Britain, perhaps we would be better off if it was the other way around. Whatever they say to get into office, when they get there the majority of elected representatives from the big parties ‘go native’. Even sincere politicians get sidetracked, and most simply disappear into a corrupted machine that tolerates crime and anti-social behaviour, that cedes more and more powers to the EU, that allows the British industrial base to continue shrinking, that presides over the dumbing-down of schools and the arts, and which permits the continued immigration of hundreds of thousands of ‘new Britons’ every year.

We live in a Britain in which there is no longer any common purpose, in which there are no common values, in which there is no long-term thinking, and which sees no permanence in anything. More and more Britons are rootless, bootless and fruitless – and are being simply crowded out of existence in the land they have occupied for millennia through uncontrolled globalisation, uncontrolled immigration, post-civilized post-modernism and punitive taxation.

More and more Britons have no faith in God, no faith in Man, and no faith in the institutions of their country. All this becomes a vicious circle of faithlessness breeding yet more faithlessness. Is it so surprising that so many people don’t get involved in politics, or even read newspapers or bother to vote – or that so many others simply leave for ever, to search for some meaning in Malaga that they could not find in Manchester? It is small wonder that the people of Britain when viewed en masse look rather like a defeated army. Could they be anything other than profoundly unhappy in the circumstances? What I – and many, many others – would like to know is who will be able to make us feel good about ourselves again.

Enlightened Enemies - The Hume - Rousseau Feud Re-Examined - David Edmonds and John Eidinow

His friend, the economist and moral philosopher Adam Smith, agreed, eulogising Hume after his death as the exemplar of as "perfectly wise and virtuous man as perhaps the nature of human frailty will permit". Historians and biographers have gone along with this image - ignoring Smith's caveat ... "as the nature of human frailty will permit" ...

That human frailty had faced its severest test 10 years earlier when Hume offered to succour the radical author Jean-Jacques Rousseau.

The year was 1766 and Rousseau had just cause to fear for his life. For more than three years he had been a refugee, forced to move on several times. His radical tract, The Social Contract, with its famous opening salvo, "Man is born free, but everywhere he is in chains", had been violently condemned. Even more threatening to the French Catholic church was Émile, in which Rousseau advocated denying the clergy a role in the education of the young. An arrest warrant was issued in Paris and his books were publicly burned.

In The Confessions, a literary landmark described as the first modern autobiography, Rousseau spoke of "the cry of unparalleled fury" that went up across Europe. "I was an infidel, an atheist, a lunatic, a madman, a wild beast, a wolf ..."

Fleeing France, he had found safe haven in a remote village in his native Switzerland. But soon the local priest began to whip up hatred against him, charging him with being a heretic. The atmosphere turned ugly. Rousseau was abused in the street. Some believed this lean, dark man whose eyes were full of fire was possessed by the devil.

One night, a drunken mob attacked his house. Rousseau was inside with his mistress, the former scullery maid Thérèse le Vasseur (by whom he had five children that he notoriously abandoned to a foundling hospital), and his beloved dog, Sultan. A shower of stones was thrown at the window. A rock "as big as a head" nearly landed on Rousseau's bed. When a local official finally arrived, he declared, "My God, it's a quarry."

Rousseau had no choice but to uproot once more. So where next? His saviour would be the Scotsman David Hume.

In October 1763, Hume had gone to the French capital as under-secretary to the newly appointed British ambassador, Lord Hertford.

Today, Hume is known above all for his philosophy, but then he was renowned for being an historian. His first philosophical work, The Treatise of Human Nature, had been, if not exactly ignored, then certainly not acclaimed as the sublime work of genius it is. But his epic six-volume History of England, which had appeared between 1754 and 1762, had become a bestseller, and made him financially independent. Turning his back on the previous mode of history writing as a sequence of dates, names and glorifications, Hume brilliantly combined character studies and the detail of events with an analysis of the broad sweep of underlying forces. The tone was thoughtful, civil, temperate. The series would go through more than a hundred editions and still be in use at the end of the 19th century.

Hume still felt, justly, under-appreciated. The "banks of the Thames", he insisted, were "inhabited by barbarians". There was not one Englishman in 50 "who if he heard I had broke my neck tonight would be sorry". Englishmen disliked him, Hume believed, both for what he was not and for what he was: not a Whig, not a Christian, but definitely a Scot. In England, anti-Scottish prejudice was rife. But his homeland too seemed to reject him. The final humiliation came in June 1763, when the Scottish prime minister, the Earl of Bute, appointed another Scottish historian, William Robertson, to be Historiographer Royal for Scotland.

The invitation from Lord Hertford must have seemed irresistible. Hume's friends travelling in France had already told him about his incomparable standing in Parisian society. And the two years he spent in Paris were to be the happiest of his life. He was rapturously embraced there, loaded, in his words, "with civilities". Hume stressed the near-universal judgment on his personality and morals. "What gave me chief pleasure was to find that most of the elogiums bestowed on me, turned on my personal character; my naivety & simplicity of manners, the candour and mildness of my disposition &tc." Indeed, his French admirers gave him the sobriquet Le Bon David, the good David.

Soon in the French capital it became social death not to be acquainted with him. In his Journal, Horace Walpole (on a prolonged visit to Paris) records, "It is incredible the homage they pay him." To a fellow historian Hume wrote: "I can only say that I eat nothing but ambrosia, drink nothing but nectar, breathe nothing but incense, and tread on nothing but flowers. Every man I meet, and still more every lady, would think they were wanting in the most indispensable duty, if they did not make to me a long and elaborate harangue in my praise."

The lavish attention paid by women must have come as a pleasant shock to this obese bachelor in his 50s. James Caulfeild (later Lord Charlemont), who'd once described Hume's face as "broad and fat, his mouth wide, and without any other expression than that of imbecility", observed how in Paris, "no lady's toilette was complete without Hume's attendance".

Hume was glorified both in court circles and in the so-called "Republic of Letters", that unique French Enlightenment territory of salons governed by outstanding women. The salons became the transmission system of the French Enlightenment, creating, focusing and broadcasting radical opinion. The female hosts were the firm regulators of tact and etiquette: they wanted the guests to shine but they could set the tone of the discussions and insist on clarity of language. Their art was the creation and maintenance of civilised conversation.

In the salons, Hume was introduced to the critics, writers, scientists, artists and philosophers who powered the French Enlightenment, the philosophes. They included the "cultural correspondent for Europe", Friedrich Grimm, and the editors of that vast compendium, the Encyclopédie, the pioneering mathematician Jean d'Alembert and the multi-talented Denis Diderot. Diderot had recognised Hume as a fellow Enlightenment spirit - a cosmopolitan. "I flatter myself that I am, like you, citizen of the great city of the world," Diderot wrote to Hume. Hume also became close friends with the passionate atheist Baron d'Holbach, a major financial supporter of and a contributor to the Encyclopédie. All four men would be crucial in Hume's quarrel with Rousseau.

One salon hostess was a vital link in bringing Rousseau and Hume together: the beautiful, clever and moralistic Madame de Boufflers, in whose dazzling salon, with its four huge mirrors, the young Mozart once performed. The intimate tone of the letters between Hume and Mme de Boufflers indicates that he, at least, became infatuated. A spell apart had Hume writing to her: "Alas! Why am I not near you so that I could see you for half an hour a day." She flattered him that she "admired his genius" and that he made her "disgusted with the bulk of the people I have to live with", ending one note, "I love you with all my heart". Sadly, Hume might have misread the silken manners of her court.

When the ambassador, Lord Hertford, was replaced, Hume's sojourn in paradise ended too. Britain beckoned. Mme de Boufflers asked him to assist the persecuted Rousseau in securing asylum in England. How could Le Bon David possibly say no?

Saviour and exile finally met in Paris in December 1765. There had, until then, been only a short epistolatory relationship between them - marked by mutual effusions of love and admiration. Here is Rousseau on Hume: "Your great views, your astonishing impartiality, your genius, would lift you far above the rest of mankind, if you were less attached to them by the goodness of your heart." After their early encounters in the French capital, Hume penned an unreserved panegyric to a clerical friend in Scotland comparing Rousseau to Socrates and, like a starry-eyed lover, seeing beauty in his adored one's blemishes: "I find him mild, and gentle and modest and good humoured ... M. Rousseau is of small stature; and would rather be ugly, had he not the finest physiognomy in the world, I mean, the most expressive countenance. His modesty seems not to be good manners but ignorance of his own excellence."

Several of his philosophe friends tried to shake Hume from his complacency. Grimm, D'Alembert and Diderot all spoke from personal experience, having had a spectacular falling-out with the belligerent Rousseau in the previous decade. In consequence, they had totally severed relations with him. Most chilling was the warning from Baron d'Holbach. It was 9pm on the night before Hume and Rousseau set out for England. Hume had gone for his final farewell. Apologising for puncturing his illusions, the baron counselled Hume that he would soon be sadly disabused. "You don't know your man. I will tell you plainly, you're warming a viper in your bosom."

At first all seemed well. Rousseau, not only a radical thinker but also one of Europe's most popular novelists, was a star in London. His arrival gave the press the opportunity to congratulate readers on this display of British hospitality, tolerance and fair mindedness. How different from the bigoted, autocratic French!

Of course it must have been galling for Hume, hailed in Paris, to be reduced, in the shrewd observation of an intimate Edinburgh friend, William Rouet, Professor of Ecclesiastical and Civil History, to being "the show-er of the lion". The lion stood out in his bizarre Armenian outfit, complete with gown and cap with tassels, and was almost everywhere accompanied by his dog, Sultan. Hume was astounded by the fuss, somewhat meanly putting it down to Rousseau's curiosity value.

He was still insistent on his love for Rousseau - at least when writing to his French friends. He told one, "I have never known a man more amiable and more virtuous than he appears to me; he is mild, gentle, modest, affectionate, disinterested; and above all, endowed with a sensibility of heart in a supreme degree ... for my part, I think I could pass all my life in his company without any danger of our quarrelling ..." Indeed, a source of their concord, Hume thought, was that neither one of them was disputatious. When he repeated the sentiments to D'Holbach, the baron was glad that Hume had "not occasion to repent of the kindness you have shown ... I wish some friends, whom I value very much, had not more reasons to complain of his unfair proceedings, printed imputations, ungratefulness &c."

Hume worked to find somewhere for Rousseau to live and to engage his friends at Court to pursue a royal pension for the refugee. Initially the immigrant was set up in rooms just off the Strand while Hume stayed at his usual lodging house near Leicester Fields (today's Leicester Square), run by two respectable Scots ladies. But Rousseau was not a city lover. London was in the midst of a manic construction boom. Fuelled by the triumphant end to the seven years war, the capital was the richest, fastest growing city on earth. It had become the lodestone for the talented and ambitious, with foreign trade producing new wealth and shaking up the class order. For Rousseau, however, the city was full of "black vapours".

He moved to the bucolic village of Chiswick to lodge with "an honest grocer", James Pullein. Then, in March 1766, the offer of a country house came from an English gentleman, Richard Davenport, an elderly patron of substantial means. Davenport had an empty mansion, Wootton Hall, in a corner of Staffordshire that seemed to guarantee the solitude for which Rousseau yearned.

En route to Wootton, the exile stopped off at Hume's dwelling in London on Wednesday, March 19 1766. It was their last meeting.

Rousseau was already seized with the glimmerings of a plot; he warned his Swiss friends that his letters were being intercepted and his papers in danger. By June, the plot was starkly clear to him in all its ramifications - and at its centre was Hume. On June 23, he rounded on his saviour: "You have badly concealed yourself. I understand you, Sir, and you well know it." And he spelled out the essence of the plot: "You brought me to England, apparently to procure a refuge for me, and in reality to dishonour me. You applied yourself to this noble endeavour with a zeal worthy of your heart and with an art worthy of your talents." Hume was mortified, furious, scared. He appealed to Davenport for support against "the monstrous ingratitude, ferocity, and frenzy of the man".

Hume was right to be afraid. He knew Rousseau was working on The Confessions: he might even have sneaked a look at early pages on the journey across the Channel. Rousseau wielded the most powerful pen in Europe. His romantic novel Héloïse demonstrated that power, leaving readers weeping and sighing. It was a publishing phenomenon: demand was so great that Parisian booksellers rented it out by the hour. Hume saw his own memory put at risk for all time. "You know," he told another old Edinburgh friend, the professor of rhetoric, Hugh Blair, "how dangerous any controversy on a disputable point would be with a man of his talents."

Hume's eyes were on France, in particular, and his reputation as the good David. His first denunciations of Rousseau were made to his friends in Paris; his Concise and Genuine Account of the Dispute between Mr. Hume and Mr. Rousseau would be published there in French, edited by Rousseau's enemies. He studiously avoided communicating with Mme de Boufflers, knowing she would, as she did, urge "generous pity". Hume's descriptions of Rousseau as ferocious, villainous and treacherous ensured joyful coverage in newspapers and discussions in fashionable drawing rooms, clubs and coffee houses. The actor-manager David Garrick wrote to a friend on July 18 that Rousseau had called Hume "noir, black, and a coquin, knave".

In his reply to Rousseau, Hume (unwisely) demanded that Rousseau identify his accuser and supply full details of the plot. To the first, Rousseau's answer was simple and powerful: "That accuser, Sir, is the only man in the world whose testimony I should admit against you: it is yourself." To the second, Rousseau supplied an indictment of 63 lengthy paragraphs containing the incidents on which he relied for evidence of the plot and how Hume had deviously pulled it off. This he mailed to his foe on July 10 1766. The whole document managed to be simultaneously quite mad but resonating with inspired mockery and tragic sentiment. It was also composed with a novelist's instinct for drama. For instance, among the accusations Hume found trickiest to deal with was Rousseau's claim that on the journey to England he heard Hume mutter in his sleep, "Je tiens JJ Rousseau" - I have JJ Rousseau. In the indictment, Rousseau played brilliantly with these "four terrifying words". "Not a night passes but I think I hear, I have you JJ Rousseau ring in my ears, as if he had just pronounced them. Yes, Mr Hume, you have me, I know, but only by those things that are external to me ... You have me by my reputation, and perhaps my security ... Yes, Mr. Hume, you have me by all the ties of this life, but you do not have me by my virtue or my courage."

Hume was aghast: he could not hope to match prose that he described to a French sympathiser as having "many strokes of genius and eloquence". What he did, instead, was laboriously to go through the indictment, incident by incident, desperately scrawling "lye", "lye", "lye", in the margins as he went along. His annotations became the basis of his Concise Account

Among Rousseau's numerous charges were Hume's misreading of a key letter from Rousseau about a royal pension. That error embroiled King George III. The king was just one of the many prominent figures to be sucked into the quarrel: others included Diderot, D'Holbach, Smith, James Boswell, D'Alembert and Grimm. Walpole became a key player. Voltaire piled in too, unable to resist the chance to strike at Rousseau.

Grimm said that a declaration of war between France and Britain would not have made more noise.

In press coverage of what the Monthly Review called the "quarrel between these two celebrated geniuses" support for Hume was far from universal. While Rousseau was denounced for lack of gratitude, the Monthly Review was not alone in advocating "compassion towards an unfortunate man, whose peculiar temper and constitution of mind must, we fear, render him unhappy in every situation". Letter writers, under cover of pseudonyms such as "A Bystander", also took up the cudgels for Rousseau: one recurring theme was the lack of hospitality and respect accorded the exile, which shamed the British nation. There was poetical support in the St James's Chronicle:

Rousseau, be firm! Though malice, like Voltaire,

And superstitious pride, like D'Alembert

Though mad presumption Walpole's form assume,

And base-born treachery appear like Hume,

Yet droop not thou ...

This even-handed treatment was not what Hume had expected, and not the version he gave Mme de Boufflers, writing that there had been "a great deal of raillery on the incident, thrown out in the public papers, but all against that unhappy man". A cartoon depicting Rousseau as a Savage Man, a Yahoo, caught in the woods was more to Hume's taste. He described it to her with relish. "I am represented as a farmer, who caresses him and offers him some oats to eat, which he refuses in a rage; Voltaire and D'Alembert are whipping him up behind; and Horace Walpole making him horns of papier maché. The idea is not altogether absurd."

So, in less than a year, the relationship between Hume and Rousseau had gone from love to mockery by way of fear and loathing.

In hindsight, it seems unlikely that they were ever going to get along, personally or intellectually. Hume was a combination of reason, doubt and scepticism. Rousseau was a creature of feeling, alienation, imagination and certainty. While Hume's outlook was unadventurous and temperate, Rousseau was by instinct rebellious; Hume was an optimist, Rousseau a pessimist; Hume gregarious, Rousseau a loner. Hume was disposed to compromise, Rousseau to confrontation. In style, Rousseau revelled in paradox; Hume revered clarity. Rousseau's language was pyrotechnical and emotional, Hume's straightforward and dispassionate. JYT Greig wrote in his 1931 biography of Hume, "The annals of literature seldom furnish us with two contemporary writers of the first rank, both called philosophers, who cancel one another out with almost mathematical precision."

While they may be described now as thinkers in "the Age of Enlightenment", how far "Enlightenment" covers a common national experience or meaning is a matter of vigorous dispute. A particular reading of French history tends to shape the general idea of "the Enlightenment" as, broadly, the French philosophes' belief that the application of critical reason to received traditions and structures would bring human advancement. The dominating Enlightenment narrative becomes a small and easily identifiable group of brilliant people, a central activity, the Encyclopédie; the sweetness of the salons balanced by the risk of imprisonment, the focus on reason, and the whole enterprise terminating in the guillotine.

But neither Hume nor Rousseau fitted easily into that narrative and its intellectual consensus. Rousseau, in particular, inveighed against so-called "civilisation", taking aim at the Enlightenment's proud boast of progress (that there had been progress in the human condition, and that with the systematic application of rationality and information, improvements could be speeded up). "Nature has made everything in the best way possible; but we want to do better still, and we spoil everything," he wrote. In his emphasis, not just on reason but on feeling, on sensibilité, he would gain a posthumous reputation as the father of the Romantics.

But Hume, too, is a problematic Enlightenment figure. He used reason to demonstrate the limits of reason and he injected his empiricism with a destructive revolutionary force. Taking empiricism to its logical conclusion, he showed how, if we rely on experience, then we can have no complete confidence in the existence of the external world; we can have no confidence in the laws of nature that we take for granted, such as gravity, and we must drastically rethink our notions of induction, necessity and personal identity. Nor could ethics have a rational foundation. Logic was an inappropriate tool for dissecting morality, like taking a carving knife to water. Reason was a slave to the passions.

True, both Rousseau and Hume assailed the Church: it might seem that in this at least they were emblematic spirits of the Enlightenment. But in fact neither did so in a way that would satisfy the wits and cynics in the salons. Rousseau believed in God's existence, professed his love for God, and his faith in God's goodness ("everything is good, coming from God"), as well as his certainty that there was an afterlife and that the soul was immortal, which "all the subtleties of metaphysics will not make me doubt for a moment".

As for Hume, though he had been damned in Scotland for having too little religion, in Paris, where he squirmed at the disdain directed at believers, his burden was that he had too much. True, he had demolished the arguments purporting to prove the existence of God, including the argument from design - the claim that only a supreme and benevolent being could explain the wonder and order in the world. This argument, Hume insisted, was untenable. How could it account for the suffering in the world? How can we infer that there is just one architect of the world, and not a co-operative of two or more?

Hume also wrote that "I would not offend the Godly". Once, dining with Baron d'Holbach, he claimed he had never seen an atheist and questioned whether they really existed. D'Holbach replied that Hume was dining with 17 of them.

For biographers, the Rousseau affair has been a sideshow in the greater scheme of Hume's astounding achievements. But Hume's behaviour is revelatory. His relationship with Rousseau and the falling-out put him under pressure, and that pressure opens up the man. Through a detailed reading of the constant correspondence, we can see that Hume had not wanted to accompany Rousseau to England in the first place - hoping to delegate that task. And, while Hume was telling his French friends of his love for Rousseau, his cousin John Home, the "Scottish Shakespeare", had noticed only 10 days or so after Hume brought his charge to London, his frustration "with the philosopher who allowed himself to be ruled equally by his dog and his mistress".